This is the last chapter from Barbara Van Orden Campbell’s journal “Bachelor Lake Daze.” Fans of Barb’s tales will be glad to know that there is more to come. As primarily an aviation history blog, we initially chose to run the aviation part of her story. Soon we will go back to the beginning, to the amusing account of the months leading up to the decision by Gold Belt Air Services to hire the Campbells to run their Bachelor Lake base.

Goose Bumps on the Grey Lake

By now it was mid-October, and we were still waiting for our freeze-up order. Alf Truchon, who managed the nearby Fecteau base, returned from a week in Senneterre, Québec, along with his dog Poune, who was a great favourite of ours. Mercifully, our groceries followed soon after, a whole Norseman load. It was a problem to find storage space for it all. Con built a cache for meat outside on the north side of the cabin. The weather turned obligingly cold and made sure that very little meat spoiled.

On the day the last plane took off into the brief November afternoon, brittle ice rimmed the shoreline and light puffs of north wind raised goose bumps on the grey, still lake. Con and I felt as exuberant as a couple of kids out of school when Norseman PAA* faded away to the south. Six weeks of freedom lay ahead – no passengers to feed, no radio skeds to keep, plenty to read and eat, plenty of fuel for the lamps, square miles of firewood, Alf for company! “What a wonderful place to be, I’d rather be me than anybody!” I sang melodiously, while Con held his ears and looked pained. “Not my fault if you’re tone deaf,” I told him and went right on singing.

*CF-PAA is now in the collection of the Canadian Museum of Flight in Langley BC awaiting restoration. To read some of the history of this Norseman, click on the link: http://www.canadianflight.org/content/the-norseman-cf-paa-story

Early shore ice surrounds the prototype Norseman CF-AYO at Lac Osisko, Rouyn-Noranda. She was owned and operated by Gold Belt from 1949 until 1951, when sold to Mont Laurier Aviation. Photo: Canada Aviation and Space Museum #3906.

Chinking the Log Cabins

We enjoyed our freedom, but there was a lot of work to do. The plane had brought in a great smelly mass of oakum with which we set about chinking the walls of the two log cabins. It seemed an endless task, but it went faster when Con and I worked in unison – he took the outside while I was stationed inside, poking and pounding the tarry strands firmly between the logs. But the logs were uneven and had been laid with such abandon that large logs were often balanced atop those of a much smaller diameter. There was one log in particular that seemed bent on my destruction. This menacing brute was about eighteen inches through and ran the full width of the cabin at a height of about seven feet, apparently defying all known laws of physics, and balancing like Doom just above my side of the bed. The log directly beneath it, and its only visible means of support, was a mere twig in comparison.

It was an act of faith to hop into bed each night and realize that a good brisk north wind could waft that darn thing right out of the wall and flatten me like a steamrollered toad. I never could decide if it was worse with the light on or in darkness and I never learned to live gracefully with it. Con teased me about it and tested it from all angles, pronounced it solid, but I noticed uneasily that he never offered to move the bed nor trade sides with me. It is true that when I inspected it from the outside, the overhang was far worse than it was inside the cabin – which soothed me until bedtime.

Joey Jacobson uses oakum to fill cracks on a fishing boat at Haines, Alaska. This is how the Campbells chinked the cabins at Bachelor Lake, Québec. Photo: Tom Morphet, courtesy of the Chilkat Valley News.

The chinking and caulking continued until both cabins were finished. No longer could a sudden gale blow the moss out from between two logs and whistle gaily as it scattered dried leaves or pine needles or snow or rain or a combination thereof all over the place until somebody stuffed up the crack with whatever was handy, be it a dish towel, an item of clothing or even my knitting.

When Alf saw Con banking the cabins outside with earth and doing a workmanlike job of it by building retaining walls of planks, he warned us quite solemnly what we were making the place so draft proof that we would have to leave the door open all winter to keep from suffocating.

“No damn chance, Alf,” said Con. “Look at those windows! There’s a draft coming in around them that could fan oats. I’ll fix them as best I can for the Winter and next Spring I’ll frame them properly. Maybe enlarge them and put in a couple more. There should be a window over the batteries. And another one along the front. You know, when we first came in here we should have had sense enough to knock this cabin down and build another one to replace it right away!”

“It would have been lots less work,” Alf agreed. “Then you would have had something to be proud of when you were finished. You’ve done well, though, and you should spend a comfortable winter now.”

Soft Crackling from the Wood Stove

The snow came, and went, and came again and the ice formed on our bay, finally working its way out across the lake. Few of our Cree neighbours dropped in now that their canoes were as useless as their dog sleds. We loafed or chipped away at winterizing the cabins as the spirit moved us. The radio was working well but we only called Rouyn twice a day to report weather and the improving ice conditions. We took long exploratory walks around the shore and once went into the O’Brien property just to have a look around. The snow was deeper now, and toward November’s end a heavy snowfall caused us to break out the snowshoes for travel in the bush.

Con brought the heating stove into the cabin and set it up next to the cook stove which put it in about the geographical center of the room. It was an uncomplicated device, being simply an oil drum on its side, with steel legs, a hole for a chimney and a big door cut in one end. It was large enough to hold a huge round of green birch which would chuckle and talk to itself the whole night through all the while keeping the cabin comfortably warm.

The first night we kept a fire in it was late in the Fall and the north wind herded snow clouds across the moon. It was a heady feeling to lie abed and hear flocks of geese talking among themselves as they flew before the wind. Their call sounded to me like the distant yelping of dogs, quite the loneliest sound in creation. Beneath the bed PAA the pup whimpered in her sleep and her tail thumped gently on the floor. On the cross-beam overhead Roger the cat brooded like a benign household god, dozing in the heat from the stove eddying up from below. A soft crackling from the banked fire, a pale shimmering patch of moonlight on the ceiling reflected up from water in a pail on the floor. Peace and utter contentment.

Con had to spend more time now at the woodpile. After he got a fair-sized woodpile established, he spent an hour or so each day dragging in spruce and birch to add to it. I took my turn with the buck saw on the limbless trees he dragged in but I needed a lot of practice not to get the saw blade in a bind halfway through a buxom log. Con took a dim view of this practice and seemed always to come around the corner of the cabin just as I was wrestling to free the twisted blade. He would watch this performance with jaundiced eye for quite a while before coming resignedly to my aid with superior male strength and cunning. The two-man crosscut was more to my liking for I felt I was doing a fine, fast job with Con pulling briskly on the other end. He soon cut me down to size, however, by saying he didn’t mind me riding as long as I didn’t drag my feet.

Drawing Water from the Frozen Lake

The ice on the bay grew thicker every day, and the ice chisel was needed to open a hole for water. This operation never failed to enchant the resident livestock. They came stampeding out of nowhere to stand in the spray of ice chips and then get down on their elbows to stare into the icy, black water with a great air of expectancy – dog tail wagging vigorously, cat tail straight up with a hook at the top. What they thought was going to emerge we never learned, but they continued to expect something momentarily.

It is surprising how much water is needed daily to supply even a small household, especially when every drop has to come in to the house on the end of the human arm. At first it seemed several leagues farther back to the cabin from the lake with two full pails than it did from cabin to lake. But Con did most of the Gunga Din bit when he wasn’t busy at some other task, so I wrote Dad that, while we didn’t have running water we did have walking water – a bit slower, perhaps, but there was plenty of it.

Taking a bath was something of a project but now no more difficult than it had been for our grandparents. The wash tub was set upon the stove and a couple of buckets of water poured in. When that was boiling the tub was set down on newspapers on the floor and cold water added until a comfortable temperature was achieved. I was fortunate in being small enough to sit down in the tub. Con, however, being built along more heroic lines, tried only once to be seated. He sat down alright, but when it came to getting out he found himself firmly wedged into the tub. He might well have been trapped there from that day to this if I hadn’t been there to haul him out.

Page from the Bachelor Lake base radio log maintained by Barbara Campbell. Norseman aircraft CF-PAA and CF-BSE were owned and operated by Gold Belt Air Service of Rouyn-Noranda. Scan courtesy of Con Campbell Jr.

Our log book covering the month of November 1950, shows a great fluctuation in weather conditions – snow, rain, freezing, melting, the bay ice-covered only to melt again. Mild, damp weather produced heavy fog over the water. Likewise, radio conditions varied widely. Although we contacted Rouyn only twice each day, the standby radio was always on and tuned to Rouyn’s frequency. Twenty-four hours of total silence would end as suddenly as it began. Rouyn would be coming in loud and clear only to be chopped off in mid-word by a blanket of silence that would last a matter of minutes, hours, or days. Just as abruptly a voice would come booming in as if an unseen hand had suddenly thrown a switch somewhere.

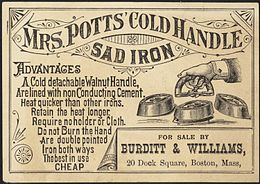

Mrs. Potts’ cold wooden handle sad iron manufactured 1876–1950 by the American Machine Company of Philadelphia. These heavy irons were heated on the wood stove. Source: Wikipedia.

It seemed incredible that the time passed so quickly. There never seemed to be enough hours to go around. I had anticipated a draggy time of it during freeze-up but there was always something to be done. The washing was no problem and I was at first most conscientious about the ironing. “Sad irons” were what we had and it soon became all too apparent whence came their name. But Alf produced a fancy-looking iron which operated on naphtha. I was secretly frightened to death of the infernal hissing machine but gingerly ironed with it for several weeks only to discover, to my vast relief, that the fumes from the dam fool thing gave me a splitting headache. So for a while I went back to clanging around with the sad irons but finally gave that up as a lost cause after scorching the seat out of my second best pair of slacks. Thereafter, except for state occasions, we wore our clothes clean, but un-ironed. It couldn’t have mattered less.

With Christmas only a month away I began to fret about Christmas cards. True I could have radioed out for a supply to come in on the first plane but I hated to burden the organization with such fripperies. So one day I seized my little axe and strode purposefully up the trail to the birch grove and set to work hewing out Christmas cards. Selecting trees with clear, branchless trunks, I cut wide strips of the bark, taking care not to ring the trees. I brought home the sheets of bark, rolled back the mattress on the bed and spread the bark flat upon the spring. A week later I drew them forth, flat and smooth, and cut the strips into rectangles to fit an envelope. Nothing to it so far…

Barbara Campbell’s journal ends here abruptly. We can only guess that she sent birchbark cards to all their friends and family members at Christmas 1950! If someone in your family ever received a birchbark card or letter, please let us know!

Acknowledgement

Thanks to Dave Arnold, Senior Manager at the Canadian Museum of Flight at Langley, BC, for providing a link to the latest chapters in the story of the Norseman CF-PAA on the museum’s website. To learn more about the museum, please visit http://www.canadianflight.org/

Recent Comments