Bomber Delivery at Record Speeds

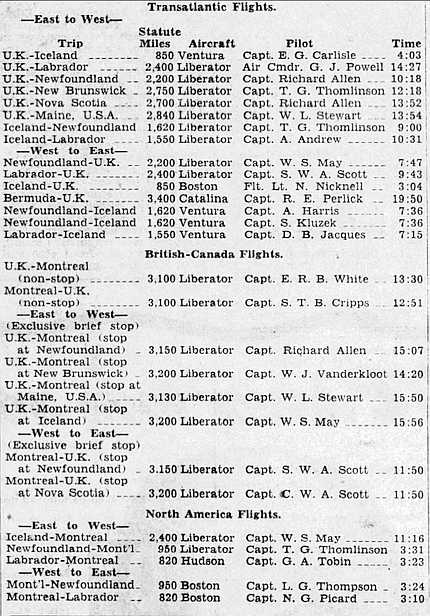

In April 1943, normally tight-lipped officials of the Montréal-based Royal Air Force Transport Command (formerly RAF Ferry Command) did the unthinkable. They broke the veil of secrecy that shrouded wartime bomber ferry operations. With great fanfare, they proudly issued a list of their fastest times in delivering North American bombers to Britain, or transporting freight and passengers across the Pond.

Canadian Breaks Record

Heading the disclosure list was a flight by Captain W. S. (Bill) May. Named to Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame in 1979 for his lifetime achievements in aviation, May covered the 1,912 nautical miles across the North Atlantic in 7 hours, 47 minutes, flying a four-engine Consolidated Liberator.

Strong tailwinds contributed to his speed. At 245.6 knots, May travelled more than twice as fast as the first non-stop trans-Atlantic fliers, Alcock and Brown. The speed of their 1919 crossing from Newfoundland to Ireland was 103 knots. In their twin-engine Vickers Vimy biplane, that trip took them 15 hours, 57 minutes. In an open cockpit.

May’s time bested the previous trans-Atlantic record of 8 hours, 1 minute set in 1942 by a Royal Australian Air Force pilot flying a twin-engine Lockheed Hudson for Ferry Command.

Both ferry pilots flew from Gander to Prestwick. Under wartime secrecy, these airports were never named in the media. Instead, they were referred to with vague descriptions such as “an airport somewhere in Newfoundland” and an “undisclosed location in Northern Britain.”

Transport Command’s April announcement also recognized a special record of 6 hours, 20 minutes established by using May’s landfall-to-landfall time — the elapsed time from when he crossed the Newfoundland coastline until he flew over the coast on the far side of the ocean.

At Prestwick airport in 1944, Captain G. R. Buxton of BOAC (left) reviews his trans-Atlantic fuel consumption with an Engineer Officer. © IWM (D 20354)

Across the Pond in 6 Hours, 12 Minutes

A few days later, in May 1943, the ferry organization revealed that Captain G. R. (“Sam”) Buxton had bested that mark with a landfall-to-landfall Atlantic hop of 6 hours, 12 minutes. Like Captain May, he was also flying a Liberator. A senior captain with British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC), Buxton had been seconded to the ferry organization in 1941.

Another BOAC captain, S.T.B. (Trevor) Cripps, set a record of 12 hours, 51 minutes, for a non-stop Liberator flight of 2,694 nautical miles from Montréal to Prestwick. Cripps had been loaned to the original ferry organization in 1940, and was subsequently assigned to Transport Command’s return shuttle. His Montréal-U.K. record was toppled on 29 November 1943 by BOAC Captain Richard Allen, also flying a Liberator on the return shuttle service. Allen covered the same west-to-east distance as Cripps in just 11 hours, 35 minutes, as reported in BOAC Services: Transatlantic Services.

AL627, an RAF Transport Command Liberator, over Montréal on return from Prestwick, Scotland, May 1944. © IWM (TR-2493)

Headwinds Slow Westbound Flights

Flying in the reverse direction is more challenging. Even today, aircraft winging their way towards North America often face fierce headwinds. In April 1943, Captain Allen held the honours for the fastest westbound trip from the U.K. to Newfoundland, with a time of 10 hours, 18 minutes. He was flying a Liberator on the return shuttle service.

Transport Command’s LB-30A Liberators had plenty of power, with four R-1830-33 Pratt and Whitney engines giving a combined output of 4800 hp. In all cases here, the Liberators carried their maximum wartime all-up weight of 65,000 pounds.

Record Chasing Forbidden

Despite the publicity given to best flight times, it was actually a disciplinary offence for Transport Command pilots to chase records.

“I do not allow this consideration to enter the mind of anyone under my command,” stated Air Chief Marshal Sir Frederick Bowhill, head of the ferry organization from July 1941 to March 1943. “It is, in fact, an offence for any of my captains to attempt to ‘beat records’ which might hazard new and valuable aircraft,” he wrote in Flying and Popular Aviation in September 1942.

RAF Transport Command’s April 1943 announcement stressed that specific flight plans were established for each aircraft, setting routes, altitudes and optimal engine speeds in light of weather information from both sides of the Atlantic. Captains were expected to adhere to these plans to ensure maximum safety, comfort and fuel economy, and to avoid unnecessary wear and tear on expensive aircraft.

All well and good. But once in the air, captains were kings. Decisions had to be made on the spot, far from the seat of authority. Relying on their skills and knowledge while observing radio silence over the ocean, ferry pilots capably dealt with equipment, weather and any other problems that came up. Would you believe they never bent the rules to indulge a competitive streak? Ha!

SOURCES

“BOAC Services: Transatlantic Services.” https://ab-ix.co.uk/pdfs/AMIL-BOAC-services-Trans.pdf

Bowhill, Air Chief Marshal Sir Frederick W., “Ferry Command,” Flying and Popular Aviation, Royal Air Force special issue, Vol. 31, No. 3, September 1942, pp. 102-104, 258.

Kitchen, George, Canadian Press staff writer, “Lower Records over Atlantic,” in the Nanaimo Daily News, 5 May 1943, p. 2.

[Pudney, John.] Atlantic Bridge: The Official Account of R.A.F. Transport Command’s Ocean Ferry. United Kingdom Air Ministry: London, 1945. Reprint 2005 by the University Press of the Pacific, Honolulu, Hawaii, pp. 52-54.

“R.A.F. Reveals Series of Ocean Hop Records,” Canadian Press, in the Ottawa Citizen, 29 April 1943, p. 11. Includes the table of flights.

Wikipedia. “Transatlantic Flight of Alcock and Brown.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transatlantic_flight_of_Alcock_and_Brown

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to Bill Clark and Ian Macdonald of the Ottawa Chapter, Canadian Aviation Historical Society, for reading and commenting on a draft of this post. Any errors or omissions remain the responsibility of the author. If you spot a problem, please let me know via the Comments box.

Recent Comments