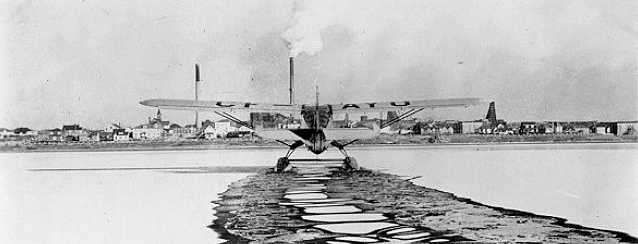

Seen here taxiing on floats through thin ice at Lake Osisko, Rouyn-Noranda, Québec, CF-AYO was the first Norseman manufactured by Noorduyn Aircraft Ltd. of Montréal. She was delivered to her original owner, Dominion Skyways, in January 1936. Gold Belt Air Service owned and operated AYO in 1950, before selling her on to Mont-Laurier Aviation Co. in April 1951. Canada Aviation & Space Museum #3905.

In August 1950, Con and Barb Campbell accepted the job of running a base for Gold Belt Air Service at Bachelor Lake, 115 miles north-east of Amos, Québec. They were kept busy refuelling the company airplanes, operating the two-way radio, providing hourly weather reports, and accommodating aircraft, pilots and passengers overnight as needed. This post is the third in a series of excerpts from Barbara’s account of their experiences, “Bachelor Lake Daze,” made with the kind permission of Dr. Sandra Campbell and Con Campbell, Jr.

To view all posts from “Bachelor Lake Daze,” click on the Gold Belt Air Service category below the main title at the top of the page.

Radio Rules the Roost

by Barbara Van Orden Campbell

With Fall approaching, it was the busiest time of the year for bush plane operators in the Canadian North. Many of the larger mining companies had exploration parties or diamond drills scattered through this undeveloped country, in constant need of supplies as they scrambled to complete their season’s work before the lakes and rivers froze over.

Planes were landing and taking off every day when weather permitted. There were frequent stopovers for meals at Bachelor Lake, and occasionally for overnight when the weather closed in or darkness overtook some aircraft that had been delayed on the swift completion of its appointed rounds. Things gradually settled down to a state of normal chaos, giving us a chance to get better acquainted with our neighbours.

There was a young couple – the Deibles – spending the summer in a neat cabin across the bay from us. He was a diamond drill foreman in charge of drilling at the Dome property about 5 miles back in the bush. His wife was a friendly girl who had spent the previous winter alone in the cabin they now occupied together. We exchanged visits during the evenings and enjoyed their company immensely. They planned to “Go Out” to civilization in the Fall but weren’t too happy at the idea.

Now and then men would come down from the exploration camps at the O’Brien or Dome properties to pick up the mail or supplies which had come in on the planes, and spend a few hours visiting with us. For all that we were supposed to be living in solitude, our cabin often bore a resemblance to Grand Central Station.

Tied to the Radio

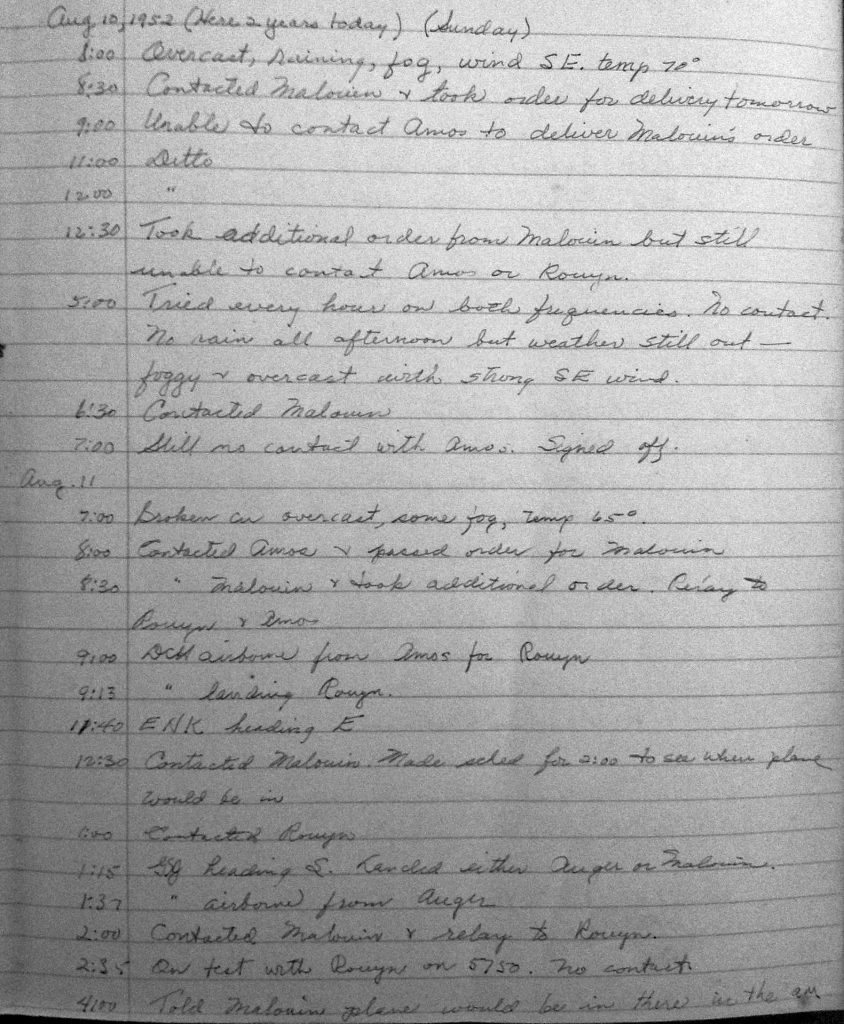

We could never wander far afield ourselves during the day because we had to stay within earshot of the radio. At the Bachelor Lake base, we were in a constant state of “radio-activity.” Every hour, we gave weather reports to the company bases at Rouyn and Amos, and we relayed messages when freakish radio conditions prevailed. Unless the weather made flying impossible, there was scarcely any time when we could turn our backs on the darn radio.

We had a small standby set which we kept tuned to the Gold Belt frequency and it was turned on from dawn until all the planes were safely roosting somewhere for the night. We were required to keep a written log of the weather and all calls made to us concerning the position of any aircraft. The Department of Transport said so, and we obeyed.

Bell River Divide

For some reason, the Bell River, lying roughly northwest-southwest, presented both a weather and a radio barrier. Weather conditions on either side of the river could be radically different and often radio beams failed to penetrate the invisible curtain. A plane flying in our direction from Amos would suddenly blare into our receiver like the crack of Doom, but we couldn’t hear a whisper out of him until he crossed the Bell. At other times we had to relay messages between Rouyn and Amos – they could both “read” us but not each other.

We soon got to recognize each operator’s voice and style of delivery and Con was able to mimic them all to perfection. From their voices we tried to visualize the individuals. We found it amazing how wrong we could be when we happened to meet one of them. Personalities emerged, even though all we ever heard in some cases was a long, dull list of supplies to be brought in on the next plane.

We knew the voice of our friend Clair, of course, and though full of business, that engaging chuckle was never far below the surface. Clair was the one who had introduced us to Gold Belt company manager Leo Seguin. Leo’s voice was soon a familiar one, too, and was characterized by a note of plaintive despair. His call of: “BSE? BSE, Baker Sugar Easy, Rouyn calling BSE, do you read me?” would bring tears to the eye of a needle.

Bob Birkett, the pilot, was no more chatty on the radio than he was when nose to nose. Sometimes our receiver got a bit off frequency and we would radio for a tuning call. All the other operators would respond with a slow count to twenty and back down again, giving us time to get the radio tuned exactly where it should be. Bob, on the other hand, would reply with “Bachelor from Amos – fivefourthreetwoone – how do you read now?” It would be all over in two seconds, even before we could reach for the tuning dial!

There was nothing private about radio-telephone in the bush. Hearing the business being conducted by parties hundreds of miles apart was like listening in on a party line telephone in the country. Or following a radio drama. At one camp, the cook was threatening to quit if certain supplies were not flown in immediately, if not sooner. At another, a mutiny was threatening if the cook didn’t quit.

Music to our Ears

As Summer drew to a close and the shadows lengthened, a strange music in the hills heralded winter’s approach. Since our arrival, we had accumulated quite a supply of 80 or 91 octane gasoline, in addition to the naphtha for our own use in the lamps and the small stove. Whenever a plane came in to Bachelor Lake with a part load or on the Thursday “milk run,” it would carry at least one 45-gallon drum of aviation gas, ensuring that we had a good supply of fuel to service the aircraft that flew in. We stored these drums on their sides, well away from the cabins, until they were needed.

The difference between daytime and nighttime temperatures became more pronounced as we moved into Autumn, and the steel drums would expand or contract as the temperature rose or fell. We were saluted morning and evening by a cannonading most impressive to hear, each barrel producing a slightly different pitch depending on how full it was. The chorus of dull booming would reverberate through the hills, signalling the changing of the seasons.

When Spring came several months later, the welcome sound of the first barrel burping in the warmth of the sun brought us a sense of jubilation akin to what the Eskimos* must feel when the sun begins to peep over the southern horizon after the long darkness of the Arctic winter.

* The term “Eskimos” was commonly used in the 1950s to refer to the indigenous people of the Arctic, but today in Canada we prefer the word “Inuit.”

Storing Gas Drums

by Con Campbell Jr.

Drums were usually stored on their sides, stacked 3 high.

When needed. they were rolled to the dock in summer or taken on a sled in the winter. Then they were stood up with the bungs at 9 and 3 o’clock with a board under the 12 o’clock position and left to sit for 24 hours. This allowed sediment and water to settle at the lowest point. Just use a soda can to see what I mean.

Then both bungs were opened and a visual check made by looking through the smaller bung. The fuel was then hand-pumped into the aircraft, strained through a funnel fitted with a large piece of felt cloth. Sometimes the pilot’s felt hat served to strain the gas.

In my time, a chamois filter was often used in aircraft with fuel injection systems such as the Cessna 185 or 206. The chamois was better, because the felt releases small threads which might block the injectors. Later on we got pumps with 2 filters built in, one a go/no go which would block if water entered the filter.

Con Campbell got his commercial pilot’s licence in 1974, and flew Otters, Beavers and Cessna 185s until he qualified as a helicopter pilot in 1978. He has been flying helicopters commercially for the past 40 years.

Acknowledgements and Links

Thanks to the Canada Aviation and Space Museum for photos from their online Image Bank; to John Davidson for enhancing Gold Belt’s letterhead and the Radio Log page; to Reg Walker for technical advice; and to Con Campbell Jr. for generously sharing background information and a page from the Bachelor Lake base Radio Log.

To learn more about the great Canadian bush plane, the Noorduyn Norseman: http://wp.me/P790K9-bp

Read a short bio of Barb Campbell: http://wp.me/P790K9-6J

Recent Comments