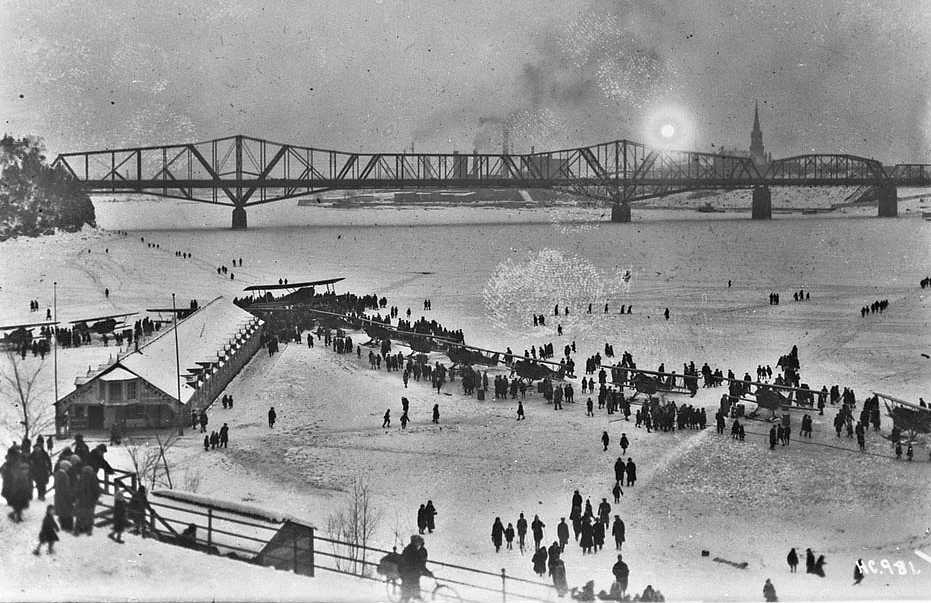

Temporary air station on the Ottawa River set up by the Royal Canadian Air Force to handle the visiting US Army Air Force planes. Photo: Library and Archives Canada – LAC PA-062320.

First Goodwill Visit by US Army Air Corps

At noon on 24 January 1927, twelve American Curtiss Hawk P-1B fighter planes swooped down on Canada’s capital. This was a friendly “invasion” – a goodwill visit by the First Pursuit Group of the U.S. Army Air Corps (AAC) from their base at Selfridge Field in Michigan. The visit to Ottawa and Montréal doubled as a cold weather test for the elite squadron. Little did they know how severe that test would be!

The US Army Air Corps purchased 93 Curtiss P-1 Hawks between 1926 and 1929. Photo: U.S. Air Force via Wikimedia Commons.

Thousands of residents of Ottawa and Hull turned out that Monday to see the visitors arrive. They were amazed by the military precision of the biplanes in formation as they winged over the Parliament Buildings and Major’s Hill Park. Moving into single file, the ski-equipped Hawks then landed on the frozen Ottawa river and taxied to a temporary air station near the shore set up by their hosts, the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF).

The flight from Detroit had taken just under three hours travelling at an average speed of 135 mph (117 kts). The slower Douglas C-1 transport escorting them landed three hours later after a refuelling stop at Camp Borden.

RCAF director Group Captain J. Stanley Scott welcomed the American commander, Major Thomas G. Lanphier, and introduced him to Canada’s Governor-General, Viscount Willingdon, and members of the Cabinet. Also on hand to greet the fliers were defence minister Col. J.L. Ralston; head of the Canadian army Major-General J.H. MacBrien; Ottawa mayor John Balharrie; U.S. consul-general Col. John Foster; and numerous other dignitaries.

After their open-cockpit flight, all the airmen sported red faces and frosty mustaches. Gratefully leaving the RCAF mechanics to drain the oil and water from their olive-drab aircraft, since their own mechanics were still en route in the Douglas transport, the pilots enjoyed lunch as guests of the Rotary Club at the nearby Chateau Laurier hotel and then took afternoon tea at Rideau Hall, the official residence of the Governor-General. Later, while they danced the evening away at the annual Garrison Ball, the Ottawa temperature dropped to -9.5°F (-23°C).

Frozen Engines Threaten Delay

On Tuesday morning, 25 January, all the engines on the American planes were frozen solid, threatening to delay their planned departure for Montréal. Help came from the City of Ottawa, which sent out its steam-thawing machine, normally used on fire hydrants, to warm up the motors one by one until the propellers could be swung.

A pleasant surprise brightened the day for the visiting airmen. Overnight, all the tailskids had been fitted with a wide, cupped shoe to help keep the aircraft on top of the snow. The rudders on five of the Hawks, damaged by the hard snow crust while landing, had been repaired and looked like new. The wide skid shoes would prevent such damage in future. “This service was only one indication of the splendid hospitality and helpfulness extended by our Canadian friends,” said the First Pursuit pilots.

Douglas C-1 transport at Ottawa, January 1927. Photo: Dept. of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada. LAC PA-062322.

Meanwhile, some 15,000 people – including children given a school holiday for the occasion – were on hand to see the visitors depart for Montréal. Providing entertainment while all the planes warmed up, two pilots, Lt. George Finch and Lt. Lee Gehlbach, put on what the Ottawa Citizen called the “greatest exhibition of aerial aerobatics ever seen in Canada.” After a dazzling array of loops, Immelman turns, half rolls, side slips and other manoeuvers, they capped off their performance by flying under the Interprovincial Bridge.

Departing in formation, the taper-winged biplanes followed the Ottawa River towards Montréal. Blinding snow squalls* forced them down twice on the frozen river. In the first whiteout, the Hawks landed in single file at a fast pace, cascading large pieces of crusted snow high into the air. Happily, the new skid shoes prevented the aircraft tails from sinking more than three inches into the snow and kept the rudders safely out of danger.

*Snow squalls often cause rapid changes in the weather from clear skies to heavy snow.

Cartierville Airport 1929. To the left is the town of Saint-Laurent, with Mont-Royal in the distance. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

After a second stop to wait out another squall, the Hawk pursuit planes finally reached the Bois Franc airfield at Cartierville, 10 miles (16 km) from Montréal. On arrival they were greeted by RCAF officers, the American Consul-General, and Montréal civic officials.

Soon the sound of a 400-hp Liberty V-1650 engine announced the arrival of the Douglas C-1 transport. But it flew past, with the pilot and co-pilot/mechanic in their open cockpit tucked almost under the upper wing leading edge. About the size of a DHC-3 Otter, the boxy transport carried five more mechanics and a Detroit newspaperman. Later a phone call advised that it had landed on Lake St. Louis near Pointe-Claire.

In the absence of their mechanics, the pilots went to work themselves preparing their machines for their all-night stay in the cold. An evening’s entertainment at Montréal’s prestigious Saint-Denis club made up for their hard work.

Winter’s Revenge

On Wednesday night, January 26, the mercury fell to -22°F (-30°C), freezing the engines solid once again. The planned Thursday departure had to be put off until Friday.

As in Ottawa, the City of Montréal helped out by sending its horse-drawn steam-thawing machine to warm the radiators. A rush order for Maple Leaf antifreeze was placed by RCAF Flying Officer Albert de Niverville. Evidently he had a persuasive touch. Before long, the sales manager for the Canadian Industrial Alcohol Company arrived in his own car with the full quantity of antifreeze. The Americans were also advised to use a low-viscosity engine oil. By the end of the day, all 12 aircraft had been fully serviced with gasoline and winter-grade oil, and 30% antifreeze had been added to the water in their radiators.

In Friday’s milder temperatures, only one of the Hawks refused to start. Leaving it behind with two others to keep it company, nine pursuit planes set out for Buffalo. However, low ceilings and heavy snow blocked their way as they crossed upstate New York. Heading north again up to the St. Lawrence River, they landed on clear ice in a dense blizzard, and arranged to overnight at nearby Clayton, N.Y.

By 9 p.m., warm south winds had washed away the snow at Buffalo airport, where they planned to land on skis on Saturday. Scouting out an alternative, a representative of the Curtiss Airplane company suggested the outer harbour at the mouth of the Buffalo River. Although the ice was rough, all nine Hawks landed there safely. Major Lanphier and his pilots then enjoyed the hospitality of Curtiss general manager C. Roy Keys, who entertained them at dinner followed by a theatre party.

On Sunday, January 30, they took off on their last leg home, all nine planes having been refuelled and checked over by Curtiss mechanics. Buffeted by 70-mph headwinds, they averaged a speed of only 20 mph (17 kts) while struggling to keep their planes upright. “At times we were blown up or down a matter of a couple of hundred feet,” said Lanphier. They finally landed at 2 p.m. on runways marked on the ice of St. Clair Lake.

Stunting by Lee Gehlbach

Meanwhile, the last three planes finally took off from Cartierville on Friday, January 28. Piloted by Lts. Arthur Leggitt, Charles Deerwester and Lee Gehlbach, they returned almost immediately after running into a heavy snowstorm. Making the most of the situation, Lt. Leggitt decided to have Lee Gehlbach put on a short stunting demonstration. They then planned to park their aircraft for the night beside the transport plane at Pointe-Claire.

Wrapped up warmly in his fur-lined suit and helmet, and wearing a chamois face protector, Gehlbach fastened on his parachute and climbed into the Hawk. Half an hour later, he told a Montréal Star reporter that the only two stunts he performed were barrel rolls and Immelman turns because of the belly tank attached under the fuselage. “That tank is for long-distance flights. It weighs 400 lbs. when it’s full of gas and that seriously hinders the stunting capability of the machine,” he explained.

“When I saw the two bridges that cross the river,” he continued, “I decided to fly under the longer one, the Victoria Bridge. It was pretty low but I thought I could get under.” It certainly was low! The clearance was 60 feet (18.3 m) according to aviation historian George Fuller, while the overall height of the Curtiss Hawk was 8 feet, 10 inches (2.7 m), leaving little room for error. “That open water beneath the bridge certainly looked cold and forbidding,” Gehlbach commented.

Problems Dog Last Three Hawks on Home Trip

Saturday morning saw the last three Hawks start for home. They did not get far. One of the planes developed a radiator leak, forcing them to land at Alexandria Bay, N.Y. After making repairs, they carried on to the Finger Lakes area but there the high pressure oil line in Gehlbach’s plane gave out. Waving his companions on, he landed on scant snow cover, and replaced the broken line from his on-board repair kit. Taking off from essentially bare ground, he reached Selfridge Field at 6 p.m. on January 30.

Meanwhile the other two Hawks had only travelled 40 miles (65 km) when Deerwester’s motor overheated. The pilots landed at Irondequoit Bay near Rochester to refill his radiator, but during their attempted take-off, Leggitt’s engine failed, and travel plans were abandoned. Curtiss mechanics sent out from Buffalo gave airframes and engines a thorough going-over and replaced the skis with wheels. You can imagine the sense of relief the two pilots felt when they finally reached Selfridge Field on February 1. The Douglas transport returned the same day.

“A Real Arctic Experience”

On return to the Detroit area, commanding officer Major Thomas D. Lanphier said he was pleased with the overall experience. He said it was “an awfully rough trip – and the best time we ever had.”

“I got more from it than all the time I spent in Alaska with the Wilkins expedition last year, and the weather was colder in Canada. It was a real Arctic experience.” Having to resort to a horse-drawn steamer to thaw frozen motors was a wake-up call. “We realized we will have to equip a transport with miniature steam-producing outfits for such winter flights in the future.”

Lanphier thanked the Royal Canadian Air Force for all their assistance, especially the new tailskid shoes, and expressed his fervent hope that the RCAF would pay a return visit before long.

The Best of the Best

The Selfridge Air Museum website notes that the First Pursuit Group would spend the next two decades dazzling the local citizenry, and the world, with their aerial feats. The group tested dozens of new aircraft in operational situations, competed with distinction in air races, and set record after aviation record. They were the elite of the aviation world,

Lee Gehlbach (1902-1975)

After earning a degree in aeronautical engineering from the University of Illinois in 1924, Gehlbach enlisted in the U.S. Army as a flying cadet. Commissioned in 1926, he was posted to Selfridge Field, and went on to Kelly Field at San Antonio, Texas, in May 1927. He left the army in September 1929 to pursue a career as a test pilot, working for such companies Great Lakes Aircraft, Seversky and Grumman. Also a racing pilot, he competed for the Bendix and Thompson trophies, and earned kudos throughout the United States for winning the 5,500-mile All American Air Derby in 1930. In 1940, he went to Britain and joined the Air Transport Auxiliary. Despite newspaper reports that he entered the wartime RAF Ferry Command, no evidence has been found to support this. In 1943, he joined the U.S. Navy. After the war, he resumed his work as a test pilot, and was rated as the No. 1 test pilot in America. When he retired, he settled in his birthplace, Logan County, Illinois.

Acknowledgements

My thanks to George Fuller, Montréal, for sharing research background; Jack Lewis of Celista, B.C. for help with technical terminology; and Martin New, Montréal, for permission to use his photo of Victoria Bridge from his fascinating website, “Montreal in Pictures,”

Sources

Fuller, George A. Downwind #111: Talk to Montréal Chapter, Canadian Aviation Historical Society, 17 May 2012. “U.S. Army Air Corps Winter Training in Canada, 1927.”

Heaton, TSgt. Dan, 127th Wing Public Affairs, comp. Selfridge Field History, 1917-1929. See “The Good Will Flight to Canada” (17 Feb. 1927) and “The Friendly Invasion of Canada” (10 March 1927). https://www.127wg.ang.af.mil/Media/Features/Display/Article/865973/selfridge-field-history-1917-1929/ Retrieved 14 March 2022.

Johnsen, Frederick. “Douglas C-1 Heads the Air Force Transport Family Tree,” General Aviation News online. https://generalaviationnews.com/2019/08/05/douglas-c-1-heads-the-air-force-transport-family-tree/ Retrieved 16 March 2022.

Government of Canada, Environment and Natural Resources. Historic weather data for Ottawa and for MacDonald College, Montréal.

Neely, Frederick R. “First Pursuit Group, Using Skis, Makes Great Flight.” U.S. Air Services Vol. XII, No. 3, March 1927, pp. 16-19.

Newspapers of the day: Chicago Tribune, Detroit Free Press, Montreal Daily Star, Montreal Gazette, Ottawa Citizen, Ottawa Journal.

Selfridge Military Air Museum, https://selfridgeairmuseum.org/selfridge-ang-history/ Retrieved 16 March 2022.

Swopes, Bryan. “2 May 1925.” Technical details on Douglas C-1 transport. https://www.thisdayinaviation.com/tag/douglas-c-1/ Retrieved 19 March 2022.

Swopes, Bryan. “25 May 1927.” Technical details on Curtiss P-1B Hawk. https://www.thisdayinaviation.com/tag/curtiss-p-1b-hawk/ Retrieved 14 March 2022.

Video of Curtiss P-1B Hawk showing aerobatics. “The Army’s new Pursuit plane flown by Lt. James Doolittle (c. 1925).” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IYro-U5zqXw

Great story – glad the crews met the same caring and welcoming as the 9/11 passenger planes in the “Come from Away” story.

You’re right, they were royally welcomed and entertained in both Ottawa and Montréal. And the RCAF, as official hosts, did a top-notch job of looking after their American counterparts.

What a thrilling story. Thank you

There is another story that could be told as a follow-up. The First Pursuit squadron under Major Lanphier was back in Ottawa for the Diamond Jubilee of Confederation July 1st, 1927, as an honour escort for Charles Lindbergh and his “Spirit of St. Louis” plane. That occasion was marred by the tragic death of Lt. Thad Johnson, who was forced out of position in the formation flight of Curtiss Hawks by prop eddies and had a fatal collision trying to regain his spot. He was given a full military funeral in Ottawa. His body was borne through the city streets on a British gun carriage draped with the stars and stripes. As the train carrying his coffin left for the United States, Lindbergh and seven of the Pursuit pilots circled overhead, scattering flowers from the air.