Gold Belt Air Service base at Bachelor Lake, Québec, showing the original cabin on the left, and the smaller cabin added around 1948 on the right. In the foreground, the company’s Norseman CF-BSG. Photo credit: Canada Aviation and Space Museum #3840.

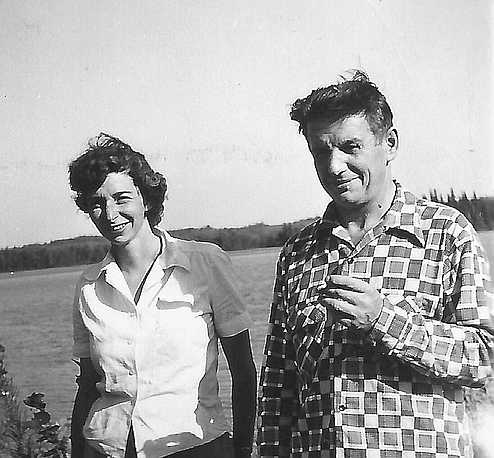

In August 1950, Con and Barb Campbell flew in to Bachelor Lake, 115 miles north-east of Amos, Québec, where they would be running a remote base for Gold Belt Air Service. They would refuel the company airplanes, keep the two-way radio operating, report the weather, and accommodate aircraft, pilots and passengers overnight as needed. This post is the second in a series of excerpts from Barbara’s account of their experiences, “Bachelor Lake Daze,” made with the kind permission of Dr. Sandra Campbell and Con Campbell, Jr.

To view all posts from “Bachelor Lake Daze,” click on the Gold Belt Air Service category below the main title at the top of the page.

Settling in at Bachelor Lake

by Barbara Van Orden Campbell

After landing Norseman CF-BSE at Bachelor Lake, company pilot Howard Watt showed the Campbells around. A small cabin had recently been built, but it was the larger original cabin that caught their attention: log walls coated in smoke-blackened grease, a sagging ceiling of grimy pink paper, and in the corner a heap of aged reeking foodstuffs. That first day they also met their neighbour Alphonse Truchon who would prove a valued friend and ally. Now it was time to settle in.

Working like ants, we hauled all the belongings we had unloaded from the Norseman into the smaller of the two cabins until we could make the larger one fit for human habitation. There was not much room left over for ourselves, but it would do for the time being. Con started the battery charger for the two-way radio while I prepared supper on the rusty wood stove in the larger cabin. As we ate, we took stock of the situation. There was a staggering list of things to be done, with each item fairly screaming for top priority.

“First thing tomorrow,” vowed Con, “I’ll set up our tent and we can move that pile of corruption to hell out of here. Howard told me yesterday that the character who was here before intended to sell that stuff to the Indians, but they would have none of it so he just flung it all in the corner and forgot it. The next priority is to get that radio working.”

The charger had been roaring away for an hour when Con shut it off and called Amos on the radio to see if we were getting out. No reply, so the charger’s staccato roar continued on into the evening.

It was after sunset when a Norseman from A. Fecteau Transport Aérien churned down the lake and tied up at Alphonse’s wharf. It would be staying for the night and I was grateful it was not one of “our” planes with a load of passengers for us to cope with in our unhinged condition.

“Just give us a week and lots of soap and hot water before that happens,” I prayed.

Radio Woes

We were to radio Amos at six-thirty in the morning to report on weather conditions. Con had a fire crackling in the stove and the coffee pot on by the time I came over from the “Other Cabin” – it was to be the “Other Cabin” for as long as we stayed there. He was just heading for the radio to make his weather report when he stopped in mid-stride, his eyes fixed in horror on the transmitter switch. It was turned on!!

With an oath that would raise blisters on a battleship, he grabbed the mike and pressed the button. Not a sound, not a flicker of the needle. Nothing. Silence.

“How in hell did I come to leave that bloody switch on last night?” he groaned and shot out the door. The charger spluttered into action. It ran all morning – without charging the batteries. Presently the plane next door took off in the misty morning light and Alphonse came over to see what all the noise was about.

“Your charger isn’t working properly – armature burned out maybe,” he diagnosed. “I’ve got a spare generator. We’ll hook it up in place of this one. If we can’t get those batteries up by noon, I’ll radio our base in Senneterre and they can phone Amos and tell them your troubles.”

I was sure we would be fired as bungling incompetents from this job we wanted so much. I could envision all of Gold Belt’s planes falling from the skies like rain because there had been no weather report from Bachelor Lake that morning.

Con and Alf tinkered and swore contentedly the whole livelong day, testing batteries, hitching up chargers, shouting into the dead transmitter, and drinking coffee as fast as I could keep it coming. At ten-thirty that night they called it a day.

Goodbye to the Chamber of Horrors

True to his word, Con set up our tent beside the Other Cabin and I bundled the entire stack of near-combustible material into it where it could reek to its heart’s content. Although the cabin floor could not be said to be actually gleaming, a ruthless assault with hot soapy water and a scrub brush had at least made it clean enough to spread with paper, and our supplies were now arranged neatly thereon.

In a moment of madness we had already torn down the horrendous pink paper ceiling, allowing air and light to circulate more freely. Alf told us it had been put up there to make the place easier to heat in the winter.

“This is a cold cabin,” he said, “It needs more chinking and double windows – and that door doesn’t fit the frame. Last winter whenever I came to visit Gaston I’d wear all the clothes I owned and then wear my packsack to keep my back warm. Gaston had a barrel stove set up next to the cook stove here and he’d sit right between the two stoves. And still he nearly froze. I think he was very glad to leave this place.”

“Well, by the holy sailor,” vowed Con, “there’s going to be a lot of changes made around this wickiup* as soon as I get this radio business straightened out!”

*Wickiup: A rude shelter or lean-to. From the Algonquian. Gage Canadian Dictionary.

An End to Radio Woes

For two days, Con and Alf wrestled with those ruddy batteries. The chargers were either snorting and bellowing outside the door, or lying dismembered all over the place. Little nuts and bolts, and other vital organs were forever dropping to the floor and disappearing down the broad crevasses between the logs. The project became an obsession with Con. His eyes glazed over and stared wildly, while his unshaven beard bristled in a manner terrifying to behold.

Help came mercifully on the wings of CF-PAA, BSE’s twin sister. She swooped down and taxied to the wharf where Con and I stood watching her approach with small cries of delight. Out climbed a radio repair man and about six and a half feet of pilot, one we had not met before. Grinning sleepily, he greeted us like old friends and seemed interested when I mentioned the pot of fresh coffee on the stove. They dragged a new transmitter and a generator from the plane, a sight we were pleased to see, but I muttered a bit about prospects for my sanity if I had to listen to three of the blasted things performing in unison.

An early Norseman, manufactured in 1940, CF-PAA served as a wireless trainer during the Second World War. The aircraft was operated by Gold Belt Air Service from 1946 until 1955. Last flown in 1972, she is now awaiting restoration at the Canadian Museum of Flight in Langley, B.C. Photo credit: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec E6, S7, SS1, P80130.

Con and the radio man were soon keening over the radio apparatus while I poured coffee. Gordon, the pilot, was a great hand at drinking coffee and downed several scalding cups while we talked. We apparently weren’t to be sacked for the radio fiasco. Leo Seguin, the company manager at Amos, had displayed stoic calm when presented with the facts.

Barb’s Apple Pie

“Don’t let a little thing like that throw you,” Gordon soothed. “You’re both doing a good job. Hell, I was in here a couple of days before you came in and the dirt and stench of this place would have broken the heart of a hyena! It looks a darn sight cleaner already and smells dandy, too. And what’s that I smell baking in the oven?” he inquired hopefully.

“Apple pie,” I told him. “It should be about done now.” I drew it, brown and bubbling, from the over. “Too bad it’s too hot for you to eat.”

“What do you mean – too hot? Just cut me a piece and we’ll soon see if it’s too hot or not!” He swung around on the bench and without rising reached up a boom-like arm and took a plate from the top shelf. “Not too big a piece,” he cautioned, “about a six-inch wedge.”

And there went a quarter of my pie. He pronounced it passable and helped himself to another serving. Then he called on the radio man and Con to get their reaction. In five minutes flat we were pie-less. Which taught me several lessons: never bake a lone pie, bake your pies in the dead of night, and never count on Gordon to forego anything remotely resembling apple pie.

Time for a Get-Away

The radio man stayed behind when Gordon took off for Waswanipi Lake to deliver mail and supplies to the bush camp there on his way back to Amos. Con and I walked slowly up the slope from the wharf. It was a honey of a day, calm and warm, without a cloud in the sky.

“You know,” Con said, turning, “we’ve been here four days and we haven’t had time to even look out the window. Let’s take one of these canoes and paddle around this end of the lake. Maybe we can find a good place to swim. Come on!”

“Yeah, but –,” I started to protest.

“Nuts!” he interrupted, “Things will be just as dirty when we get back, so don’t fret. That radio chap doesn’t need me and the plane won’t be in to pick him up until late this afternoon. This double-ender here looks like a safe bet.” He kicked at a sporty looking green canoe. He lifted it easily and carried it to the water while I ran for the paddles we had found under the “Other Cabin.” The canoes had been left behind by various companies who found it cheaper to abandon them than to ship them out by air freight.

We spent an idyllic couple of hours paddling lazily along the shoreline, exploring little coves and the mouths of small rivers, and watching muskrats swimming about their business with great efficiency. Once I nearly jumped overboard in alarm when a beaver in the dark reflections along the shore smacked the water with his tail so hard that I was certain we had hit a mine.

Company for Dinner

We got back to the cabin to find the radio man chattering happily with Leo in Rouyn, the needle on the new transmitter fairly bursting with vitality. Con talked to Leo and so did I. We were elated to have the radio in working order again and to be back in touch with the Outside World. While the radio man paddled down the lake to swim, I prepared dinner with great care, for BSE was due in at five-thirty and we therefore would be having company for the first time at Bachelor Lake.

When Howard landed, he said he supposed we’d had enough of this kind of life in the past four days to last us a lifetime. He expected we were ready to fly back out with him. Shaking his head at our blunt refusal, he sat down at the table and proceeded to eat enough for four men, pouring ketchup indiscriminately over everything on his plate. So much for my careful dinner preparations!

Thank you Con for sharing your Mom’s stories. I remember her well from her days in the Noranda Lab with my Mom. Best regards to Sandra. Hope you are all well.

Funny story not in the book.

One fine day Dad and George Pauli are on the dock refueling a Norseman.

Mother leaves the cabin to visit the outhouse. 3/4s of the way up the path she runs into a skunk. Mr. Skunk promptly sprays Mom. Mom screams and makes a dash for the outhouse and slams the door only to be confronted by the skunk’s wingman who goes full defensive and also sprays her. Mom screams again, exits the outhouse and proceeds via direct to the lake at maximum speed and dives in.

The boys on the dock had heard the first scream and looked up as Mom entered the outhouse, heard the second scream and witnessed the rapid trip to full immersion in the lake.

George looks at Con and asks: “Barb been feeling OK lately?”

Then the smell hit them.

Much laughter from the dock. Much unladylike cursing from the “Lady of the Lake”.

Great story, Con – as yours always are!

Diana

PS) The name of Robert Birkett came up as I was researching Second World War B-25s in Australia. Must be the same man as the Gold Belt pilot. If anyone has information about him, please get in touch via the Comment box.

Oh my, I can’t even imagine!! That’s funny and yet not. Thanks for sharing this story Con!

thank you thank you love it want more of it I just came across it and I am very glad I did and will be looking for more of it each and every time that it is posted on here and also I am a pilot I owned a 172 cessna skyhawk 1971 wheels and floats not all together wheels in the winter and in the spring floats thank you so very much for the work of putting it together for all of us in the aviation world its the only way to go I only wished in my younger days I could of been a bush pilot living in ALASKA thank you so so much Mr CLIFFORD C BENJAMIN COMING TO YOU FROM POLAND MAINE I USE TWITCHELL IN TURNER MAINE AND THIS IS WHERE I BOUGHT MY PLANE FROM IT DID NOT COME WITH FLOATS BUT THEY PUT IT ON FLOATS FOR THE SUM OF $14,000 DOLLARS

Barbara Campbell is getting quite a fan club! Thanks to all of you who have written with your enthusiastic reactions to posts from her “Bachelor Lake Daze.” There’s more to come – I only wish she had written about the whole 3 years the Campbells lived at Bachelor Lake instead of just August to November of the first year. But aren’t we lucky to have that much?

What a lovely job you have done on this — my mother would be so pleased. I only wish she were here to meet you as you two would greatly enjoy long chats!

Thanks so very much, and I hope we can meet in Perth next summer when my brother is visiting us

With warm wishes,

Sandy Campbell

Sandy, It means the world to me to know you are happy with the Bachelor Lake posts. Your brother has urged me to include the lead-up to the Bachelor Lake work. I’ve promised to do this. Barbara will have an even larger fan club then! I look forward to meeting you later this year in Perth.

Great memories! Glad she took the time to do this. Brings back many memories of being in the bush.

Wonderful story, and didn’t she write well, had me by the second paragraph, that damn radio. Aviation history really is the people, the planes get a lot of attention but the people stories are the ones we remember.

Ian

Vivid recounting of the activities at Bachelor Lake. The Campbells must have been an industrious – and endearing – couple. Interesting part of Quebec aviation history.