The 1920 first flight across Canada was a bold project of the Canadian Air Board to inspire the nation about the potential of aviation in peacetime. Part 1 of this story covers the seaplane flight from the East Coast to Winnipeg, while Part 2 traces the flight by landplanes from Winnipeg to the West Coast.

How would you like to fly across Canada in an open-cockpit aircraft? In October? Sounds like a crazy idea.

One hundred years ago, in October 1920, a group of young Canadian government aviators did just that.

That trans-Canada flight took 49 hours and seven minutes of flying time and covered 3,341 miles at an average 63 mph ground speed. How times have changed! Today’s jet flies at 500 mph ground speed, and takes just six hours to cross the continent.

The 1920 flight was a record-breaker on three counts. It marked the first time anyone had flown all the way across Canada. It was the first flight across Lake Superior. It was also the first time a seaplane had visited Central Canada.

They Had a Dream

Those youthful airmen had a dream. With the First World War behind them, they believed that aviation could serve post-war Canada. Their cross-Canada flight, using a series of seaplanes and landplanes, was planned to open the eyes of the public, businessmen, and particularly politicians to the potential of aviation.

Their bold scheme won approval from officials at the Canadian Air Board (CAB). This organization had been set up by the government in 1919 to manage aviation in Canada. Three senior CAB officers, all in their early thirties, would play key roles in making the dream of a trans-Canada flight a reality: Lt. Col. Robert Leckie, CB, DSO; Air Commodore Arthur K. Tylee, OBE; and Lt. Col. J. Stanley Scott, MC, AFC.*

*Top lifetime honours.

They Had a Scheme

Plans for the flight were discussed during the spring and early summer. Political changes may have impacted the planning.

In July 1920, Sir Robert Borden retired as prime minister. He was replaced as leader of the Unionist Party by Arthur Meighen, who thus became prime minister of Canada. In the new cabinet formed by Meighen there was no longer a minister of aviation, indicating a shift in government priorities. Despite this, plans for the trans-Canada flight went ahead.

In August 1920, the division of responsibilities was approved by the Air Board. Leckie, superintendent of civil flying operations, was to pilot the first half of the route, from Halifax to Winnipeg, in a seaplane, while Tylee, head of the Canadian Air Force (CAF), would direct the landplane section from Winnipeg to Vancouver.

Scott’s role was logistics. He would arrange landing spots or moorings, organize gasoline and oil supplies, and establish wireless ground communication along the entire route. Relief planes would be stationed at intervals to take over from any disabled aircraft. Coordination with local authorities was also his responsibility. As superintendent of the certificate branch, Scott held a position that would later be known as controller of civil aviation.

Behind the team of leaders were all the unsung heroes, notably the air mechanics who worked to keep the aircraft flying and the relief pilots on standby with backup aircraft.

They Had Problems

According to the original plan, Leckie and his co-pilot, Squadron Leader Basil D. Hobbs, DSO, OBE, would fly one seaplane, a Fairey IIIC floatplane (c/n F.333), Canadian-registered in October 1920 as G-CYCF, all the way from Halifax Harbour to Winnipeg. An equal-span biplane powered by a single 375 hp Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII engine, this aircraft already had an interesting history.

One of 30 examples of the IIIC design listed in the Fairey Aviation company profile, it was taken on strength by the Royal Air Force in November 1918 (RAF serial N9256). Fairey subsequently bought the aircraft back for use as a company demonstrator and registered it in Britain as G-EARS.

Modifications were made to equip G-EARS for long-range flight to vie for the 1919 Trans-Atlantic prize of £10,000. However, Fairey pilot Sidney Pickles withdrew after another contender, Harry Hawker, went down at sea. “I prefer to lose the prize and the race rather than my life,” said Pickles. (Hawker and his navigator were subsequently rescued.)

The aircraft was then sold to Canada through the Aircraft Disposal Company for use in the trans-Canada flight. Extra gas tank space had been added in Britain, reportedly giving a range of 3,000 miles. The seaplane also sported Fairey’s patented variable camber wings, enabling a 120 mph cruising speed easily reduced to the slower specified landing speed.

Newspapers reported the Fairey’s arrival in Canada by sea in early September 1920. The contract for re-assembly went to Canadian Vickers in Montréal. In the third week of September, Leckie and Hobbs, both veterans of the Royal Naval Air Service, arrived to fly the Fairey east to the Dartmouth air station near Halifax. Thus began a litany of problems that would push the start of the trans-Canada flight back from the original September date.

Its touted long range capability had made G-CYCF a natural choice for a non-stop flight from Dartmouth to Winnipeg. Tests in Montréal ruled this out. The aircraft was unable to take off with the full load of fuel. A new flight plan had to be drawn up, with added refuelling stops.

On 29 September, after further work on the aircraft by Vickers, the Air Board pilots took off for Dartmouth. Outside Fredericton, they ran into dense fog, and for safety’s sake set down on the Saint John River. Heavy rain ensued, damaging the ignition system. Two Air Board mechanics were called in, and five days later repairs were complete.

Another problem immediately faced the pilots: numerous logs floating in the river thanks to the local lumber industry. To avoid the hazards, the Fairey was towed to Fredericton where a clear run could be made for take-off. Then they discovered a leaking float that had to be repaired.

Leckie and Hobbs finally reached Halifax Harbour on October 5. Bad weather prevented flying the next day. In the end, it was 8 a.m. on October 7 when they lifted off on the first leg of the trans-Canada flight.

Fairey IIIC floatplane G-CYCF was seriously damaged while in flight over New Brunswick in October 1920. Photo: RCAF.

Flight from Hell

It turned out to be the flight from Hell. Looking back, Leckie told the Vancouver Daily World: “For flying purposes, the weather could not have been worse. We ran into a 50-mile gale in the Bay of Fundy and ran into fog several times, all the way up the St. Lawrence.”

At 10:47 a.m., Leckie dropped a message over Saint John, New Brunswick: “Bucking a 40-mile north-west wind; machine and engine OK.”

Then the winds picked up, and things changed for the worse. Leckie was later quoted by the Canadian Press: “The cowling was hurled violently backwards, missing the passengers by inches, cutting the petrol pump… and wrecking the [wooden] propeller.” Control was no longer possible.

Mustering all his skill, Leckie set the floatplane down on the Long Reach of the Saint John River at 11:05 a.m. The forced landing collapsed a float strut. Badly damaged, the Fairey IIIC was unable to complete the rest of the flight, and in fact was never flown again by the Air Board. Leckie said afterwards it was a wonder no one was killed.

Newspapers of the day featured Leckie in a starring role in the series of flights from Halifax to Winnipeg. Leckie himself, speaking in Vancouver at the successful conclusion of the entire flight, singled out Hobbs for praise and referred to him as “the pilot from from Halifax to Winnipeg.” To loud applause he added, “There is no better seaplane pilot in Canada than Hobbs.” [Paragraph added 2 Nov. 2020.]

Flying Boat to the Rescue

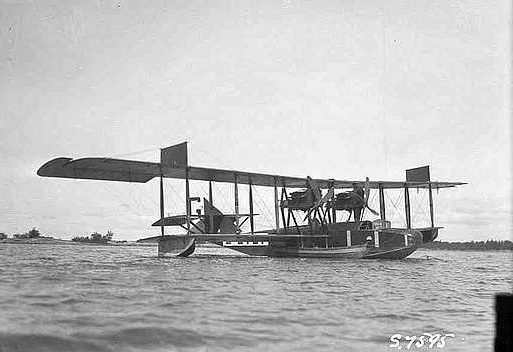

A call for help went out to Squadron Leader A. B. Shearer, superintendent of the Dartmouth air station. He set out at once in a Curtiss HS-2L flying boat, G-CYAG (ex US Navy A1941). This was one of twelve HS-2Ls donated to Canada by the United States in 1919 after the war. A pusher-type biplane, the HS-2L had a wing span of 74 feet, 1 inch, and a 360 hp Liberty engine delivering a cruising speed of 65 mph.

Shearer had his work cut out for him that day. The weather had not improved, especially in the Bay of Fundy. For four hours, with the help of his air mechanic, he battled both rough air and a severe cramp in his thigh due to an old war wound.

When the HS-2L landed beside the downed Fairey IIIC, the stranded pilots lost no time. They immediately transferred their gear to the flying boat and took off for Fredericton, New Brunswick, 45 miles away, leaving Shearer to have the floatplane dismantled and sent by rail to Dartmouth.

Leckie and Hobbs touched down in the HS-2L at Fredericton just after sunset. An hour later, their fuel tanks refilled, they were in the air again, following the Madawaska River to Lac Témiscouata. They then flew north to Rivière-du-Loup, relying on compass readings to guide them through the mist and worsening weather.

The HS-2L flying boat G-CYAG sets down at Rivière-du-Loup, Québec, on October 7, 1920. Painting by Robert W. Bradford. Photo: CASM-1967.0885.001.

Driving Rain, Welcoming Crowds

As an aid to landing, local authorities had anchored lighted buoys to mark the channel on the St. Lawrence River but the exceptionally high tide that night swamped the buoys and they had to be reset. Hobbs, at the controls for this section of the flight, brought the HS-2L down on the river in darkness and driving rain.

Leckie confided to the Ottawa Journal that he did not care for night landings. “If there’s anything I hate doing,” he said, “it is landing in the dark,”

At the town wharf, a large crowd of townspeople greeted the aviators who were “in good spirits, though feeling a little fatigued,” according to a Canadian Press report.

“A little fatigued?” It was 15 hours since they had left Halifax Harbour, including 7 hours in the air facing strong winds, equipment problems, and 3½ hours of night flying, not to mention rain that chilled them to the bone.

High Seas Challenge Take-off

Ready and waiting for them was a change of aircraft. A larger flying boat, the twin-engine Felixstowe F.3 flying boat G-CYBT (ex RAF N4016), had been ferried down from Montréal by Flight Lieutenant H. A. Wilson, DFC. Part of Britain’s post-war Imperial Gift of aircraft to Canada, this aircraft would now, they hoped, take them all the way to Winnipeg.

Leckie and Hobbs once again transferred their gear to a new plane but there was no let-up in the storm. Wilson had earlier telegraphed Air Board headquarters in Ottawa with the warning: “Very strong north-west wind and heavy sea running.”

Thunderstorms dictated an overnight stay at Rivière-du-Loup. At this point, air mechanic C.W. Heath joined the crew. He would serve as flight engineer on the trip to Ottawa and on to Winnipeg.

Next morning, the thunder finally let up but high winds were still raging. Braving the weather in their open cockpit with only a windscreen to shield them, the men revved up the Felixstowe’s engines for take-off. The rumble of the two 345-hp Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII engines must have given them confidence as high waves crashed over the top plane of the flying boat. They could also count on the lift provided by the flying boat’s 102-foot wing span and substantial wing area of 1,432 square feet to assist their take-off.

Once airborne, they found the ceiling was low at 300 feet all along the St. Lawrence, and they encountered more rain and heavy fog. Flying the HS-2L, Wilson accompanied them as far as Trois-Rivières, providing a friendly escort. The HS-2L then returned to Dartmouth.

Sunny Skies to Ottawa

Passing over Montréal, Leckie and crew paid their respects by circling twice around the seaplane base at Longue Pointe. Sunny skies finally smiled on them as they turned up the Ottawa River.

At the new CAB Ottawa air station at Rockcliffe, the only one in Canada then able to handle both landplanes and seaplanes, a landing area had been cleared on the river. Air Board personnel had carefully removed deadheads from the water to ensure the plane could land without damage.

An Ottawa Journal reporter commented on the hum of the Felixstowe’s four-bladed propellers and the glistening cherry-wood colour of the polished hull as the flying boat alighted just after noon on October 8. An extra army of helpers was needed to pull the large aircraft alongside the temporary dock set up on the river bank.

On hand to meet the aviators were several Air Board officials, including chairman Col. O.M. Biggar, secretary J. A. Wilson and CAF inspector-general Air Vice-Marshal W. Gwatkin.

Hopes of a quick departure were short-lived. Trouble with the port engine had reduced the engine speed by some 25 percent. Mechanics worked all night to strip the motor down. Finding only minor issues, they settled for a change of spark plugs and a tune-up.

Seaplane Startles North Bay Residents

At 8:45 a.m. on October 9, Leckie and crew lifted off from Rockcliffe, carrying extra gas on board.. G-CYBT circled the city, then headed up the Ottawa River to Mattawa, before turning west to North Bay on Lake Nipissing.

Bedrock delta of the French River where it flows into Georgian Bay, on Lake Huron. Photo: Ontario Parks.

Their arrival at North Bay startled local residents, few of whom had ever seen an aircraft, as Leckie recalled in a 1959 radio broadcast. After dropping a message to be telegraphed to the Air Board, “Making a good 50 miles per hour,” and waving to onlookers, the fliers swung out over Lake Nipissing and headed west to the French River.

Flight Lieutenant G.O. Johnson, who was then superintendent of the CAF Camp Borden air station, had joined the crew at Ottawa. As navigator, his job was to guide the flight to Winnipeg over the rocky forested terrain and the countless waterways of Northern Ontario, and to ensure a safe route across Lake Superior.

From Lake Nipissing, the French River led them to Georgian Bay. Leckie would later comment on the challenges of navigating this section where the many small lakes and islands made it hard to be certain they were on the right course.

Flying along the north end of Lake Huron, they headed for Sault Ste. Marie, passing over Manitoulin Island, the world’s largest freshwater island, and the town of Thessalon, on the mainland.

Superior Crossing

Coming in to Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, at 4:35 p.m. on October 9 after almost 8 hours in the air, they docked at the Imperial Oil wharf on the St. Mary’s River, now the site of the Heliport.

“The reception given the intrepid occupants of the plane was a hearty one,” the Sault Star reported. “The large crowd pressed around the aviators admiringly, while cameras and moving picture machines clicked.” A special welcome was no doubt reserved for Hobbs, who had come to live in this northern city as a child in 1900.

Air mechanic J. E. Davies had been awaiting the Felixstowe’s arrival. By the time he finished servicing the engines, it was midnight, and dense fog had settled in, ruling out further flying.

The crew caught some rest and optimistically made a night departure at 2:30 a.m., only to be turned back by lingering fog. They spent the rest of the night in the flying boat, as Leckie later told the Vancouver Province, “in the middle of the St. Mary’s River, completely surrounded by fog.” [Sentence added 2 Nov. 2020.]

Finally the fog lifted. October 10 proved to be a day of achievement, as the Air Board crew made the first flight across Lake Superior. Pilot wisdom suggests they hugged the northern shore, avoiding a direct crossing of this immense lake whose waters have a frigid average October temperature of 42°F.

The clock had just struck noon when they reached the Lakehead. Without stopping at Port Arthur (now part of Thunder Bay), they few westward over the then-uncharted lakes, rivers and islands of Northwestern Ontario, following the “iron compass” of the Canadian Pacific Railway line.

Lake of the Woods, Kenora, Ontario, seen from the air in 1948. Photo: Toronto Star Photograph Archive, Courtesy of Toronto Public Library.

First Seaplane at Kenora

Just before 3 p.m. local time on October 10, they landed at Kenora. This was yet another record, the first time a seaplane had flown over central Canada.

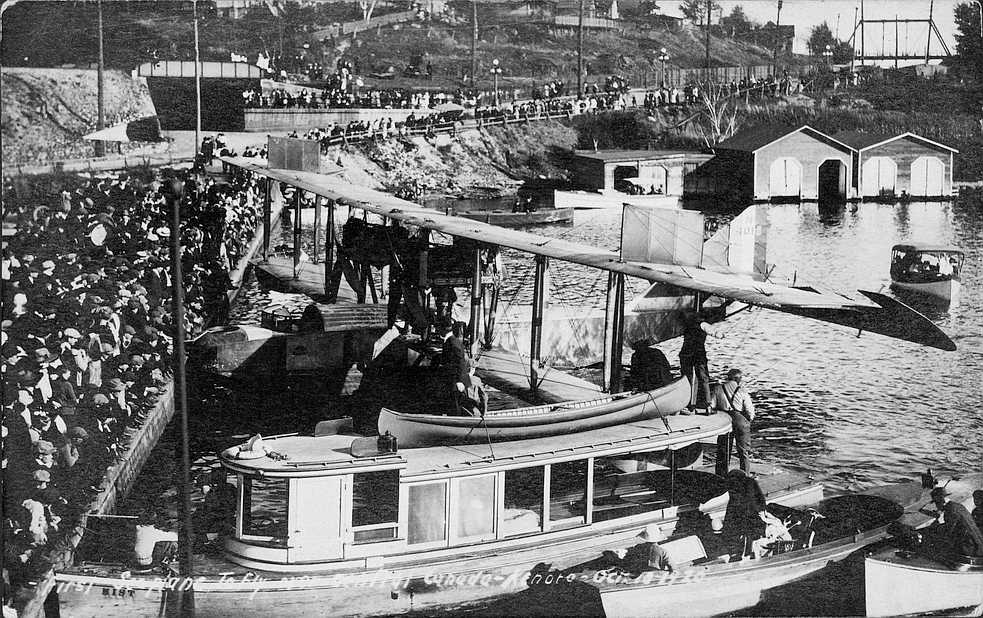

The Kenora Miner and News chronicled the arrival of Leckie, Hobbs and crew in their “giant seaplane.”

A great crowd had assembled on the docks and every vantage point along the bay front, and as the little speck was noticed in the sky to the east, gradually becoming larger and larger, the hundreds of people waited in expectancy. The sounds of the engine and propeller became distinct as the seaplane reached the outskirts and to the delight of all made a great circle above the town. It then gradually descended and lighted gracefully at almost the exact spot in the bay chosen previously. It then skirted up the bay and returning tied up at the government dock, where the gallant airmen were given a hearty reception by the crowd.

Crowds welcome the first seaplane to fly over Central Canada. Felixstowe F.3 G-CYBT at Kenora, October 10, 1920. Postcard. Collection of Ian Macdonald.

Water Route to Winnipeg

Sunset was long past when they took to the air again. Further issues in the port in-line V-8 engine had demanded attention. Departure was delayed while repairs were made to a leaking radiator, a sticky inlet valve, and a broken spring on another valve. With the troublesome engine restored to working order and refuelling taken care of, Leckie and crew resumed their journey.

From Kenora, they followed the Winnipeg River towards Lake Winnipeg until they reached a point where the crew “gauged the hop to the Red River safe,” as the Winnipeg Tribune reported. The Red River led them south towards Winnipeg. They later described how shimmering reflections of the sky on the river’s surface created a path for them.

Heavy ground mist defeated them at Selkirk, and they set the substantial flying boat down at 10:45 p.m. local time on October 10, just 30 miles short of their destination.

Air Commodore Tylee would later comment on the perfect landing made by Leckie. “He landed in the narrow Red River at Selkirk last Sunday night when it was black as pitch, with an F.3 machine that has a 105-foot span and did it without a mishap. It was a wonderful landing.” All the more so, as other accounts revealed that Leckie had had to avoid colliding with a river dredge whose outlines were obscured by the fog. [Paragraph added 2 Nov. 2020.]

Disappointment reigned at St. Vital where some 5,000 people had gathered to welcome them. Searchlights had been set up next to the fire station to illuminate the entire section of the Red River where the plane was to alight, and 18 flare barrels placed along the river banks to provide extra lighting, reported the Winnipeg Evening Bulletin.

When word came that the Felixstowe had landed at Selkirk, a gloomy pall fell over the crowd. People who had waited patiently for hours had no choice but to pack up their hopes and head for home without setting eyes on the trans-Canada fliers.

Donna and Wilfred Morier and St. Vital police/fire chief H.E. Rose standing on the bank of the Red River in Winnipeg in front of the Felixstowe F.3 G-CYBT. The flying boat landed behind the St. Vital fire hall on October 11, 1920. Photo: St. Vital Historical Society.

Closing the Loop

The crew were taken into Winnipeg, where they spent Sunday night at the Fort Garry Hotel. One last task remained. They still had to close the flight loop to Winnipeg.

On October 11, Leckie and Hobbs made the half-hour flight to bring G-CYBT to St. Vital in Winnipeg, arriving at 1:30 p.m. At last the people of Winnipeg had their opportunity to see the Felixstowe in flight and to admire the handsome flying boat.

G-CYBT’s arrival in Winnipeg completed the first half of the trans-Canada relay flight. The second half would be made by landplanes. Having finished the immediate project, Leckie boarded the train for Vancouver to be on hand for the arrival of the DH-9A flying the last segment of the 1920 trans-Canada flight.

Felixstowe Stays in Manitoba

Hobbs stayed behind in Winnipeg to deal with the Felixstowe F.3’s future. Original plans were to fly G-CYBT back east on an unhurried flight to make a detailed survey of the route.

Before the aircraft could leave, however, the engines needed a complete overhaul to resolve critical problems such as loss of compression due to damaged valves. Departure dates were set, test flights made, and departures subsequently postponed when further repairs were needed.

Finally it was too late in the season to take the flying boat east. G-CYBT was dismantled and placed in storage on the bank of the Red River. In 1921, the aircraft remained in Manitoba doing surveys and mapping work for the government, and stayed on in 1922 working in northern Saskatchewan. G-CYBT was retired in 1923 and struck off strength.

Coincidentally, in 1921 Hobbs was appointed superintendent of the Winnipeg air station, overseeing forestry work and fire control operations.

Leckie Reflects

Looking back on a series of flights that covered half a continent, Leckie told the Winnipeg Tribune that although there had been disappointments, delays and hardships, they had demonstrated that a trans-Canada flight was truly feasible. He was sure that this first flight across the Dominion would prove immensely valuable to the future development of commercial aviation in Canada.

“I confidently expect that crossing Canada by airplane will be a very common occurrence in five years,” he said. He felt, however, that traversing Canada in a single plane would never become a reality. He reasoned that seaplanes would be needed in the eastern part of the country to take advantage of water harbours, while landplanes would be needed over the Western provinces.

Leckie, of course, made these remarks when aircraft design was still in infancy, and when airfields in Canada were few and far between, and were quite literally rough fields where cows were known to savour the taste of the dope lacquer then used to treat cloth-covered aircraft wings.

Overall, as Leckie said in an interview with the Vancouver Province on October 15, the scheme was very successful. One of the main purposes was to find the best air route across the country. He believed they had done that as far as Winnipeg, and only small adjustments would be needed. “We found that it was a perfect seaplane route as far as North Bay,” he said, but beyond that point the large number of small lakes and rivers made it difficult to visually navigate the right route. The Air Board would follow up in the months ahead by producing detailed air route maps, forerunners of today’s aeronautical charts. [Paragraph revised 2 Nov. 2020.]

Courage, Daring and Resourcefulness

The last word can be left to the Winnipeg Tribune, whose editorial writer embodied the growing sense of national pride and identity in Canada when he penned these words:

Whatever men dare, they can do.

This Trans-Canada flight has an interest for the average citizen which is not commercial. The appealing, startling thing is the courage requisite to navigate the air for hundreds of miles over the wilds of Canada.

….No matter the final commercial value of the Trans-Canada flight, it is further evidence of the fact that there is in the blood of Canadians a daring and courage which is all but limitless, and an applied resourcefulness which makes a nation feel strong and resolute.

– Winnipeg Tribune, October 11, 1920, p.4

Revisions as noted in situ made 2 Nov. 2020.

Acknowledgements

My thanks to Col. (Ret’d.) John Orr, volunteer researcher with the Shearwater Aviation Museum, for motivating me to write about this important event in early Canadian aviation history, and providing background information. Thanks also to George Fuller, Bob Grant, Walter Hill and Ian Macdonald for sharing historical and technical insights, and to both Ian and Bob for reading and commenting on a pre-publication version. The author of course is solely responsible for any errors of fact or interpretation. If you spot something that should be corrected, please let me know through the Comments box.

Special thanks to the St. Vital Historical Society in Winnipeg for permission to use their photograph. Please visit their website or their Facebook page.

Sources

This artcle draws on many newspapers of the day as well as resources listed below, except as noted.

Cable, Ernie. Shearwater Aviation Museum Historian. “Felixstowe F3 Flying Boats in Canada.” WARRIOR Magazine, Shearwater Aviation Museum Foundation, Shearwater NS, Spring 2015, pp. 5-6. https://samfoundation.ca/Archived%20Newsletters/Spring-2015.pdf Retrieved October 8, 2020.

Douglas, W.A.B. The Creation of a National Air Force. The Official History of the Royal Canadian Air Force, Vol. II. Toronto: University of Toronto Press in co-operation with the Department of National Defence, 1986.

Ellis, Frank H. “The C.A.F. Trans-Canada Flight of 1920.” In Canada’s Flying Heritage. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1954. Paperback edition, 1980, pp. 180-185.

Halliday, Hugh A. “The Imperial Gift: Air Force, Part 5.” Legion Magazine, September 1, 2004. https://legionmagazine.com/en/2004/09/the-imperial-gift/

Hitchins, F.H. Air Board, Canadian Air Force and Royal Canadian Air Force. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 1972. [Thanks to G. Fuller for look-ups.]

Manning, Wing Commander R.V., Director of Air Force History. “The First Trans-Canada Flight – 1920.” Canadian Geographical Journal, September 1964, Vol. 69, No. 3, pp. 78-87.

Library and Archives Canada. “Flight – Trans-Canada, 1920.” RG24-E-1-a. [1] 1919-1920: Vol. 4888 File, 1008-1-35 Parts 1-3; [2] 1920-1942: Vol. 4889. File 1008-1-35 Parts 4-7. [Not consulted due to restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic.]

Mallott, Dick, with updates from John Orr. Canadian Aerophilatelist, September 2020, No. 124, pp. 11-16. “First Transcanada Flight Halifax to Vancouver – 7th to 17th October 1920.”

Walker, R.W. “Canadian Military Aircraft Serial Numbers: The Air Board Years. Detailed list G-CYAA to G-CYCZ.” http://www.rwrwalker.ca/cab_detail_aa_cz.html Retrieved October 7, 2020.

I love this article. Robert Leckie was my grandfather’s cousin, born in Glasgow in 1890. He’d collected another couple of medals during WWI DSC and the DFC. From what I know about him already he was incredibly brave, though perhaps the bravest thing he did was to land his flyiing boat (Curtis H12) in the middle of the North Sea to rescue the two airmen in a land plane (DH4) that had been shot down by the Germans from drowning, knowing that the overloaded also stricken flying boat wouldn’t be able to take off. He started “taxing towards England”, That took 3 days and nights until they were all picked up by rescuers who worked out where they would be from a message round the leg of the last carrier pigeon they’d released . ( The pigeon had collapsed and died on landing near the base at Great Yarmouth).

I’ve always thought what an incredible feat it was to fly over the vast watery flatlands of Canada in those days, even more having seen all the detail in this article.

Susan, I’m so glad that you connected with this article. What a pleasure to receive your comment. Hearing from family members of people featured in articles on Flights of History is the greatest reward.

Air Marshal Leckie certainly had a long and distinguished career. You probably have seen his page in the Canadian Aviation Hall of Fame.

You might also like to check out the RCAF Association Honours and Awards page on his career produced by eminent aviation historian Hugh Halliday.

I have, Diana , and thanks for your suggestions .I was fascinated to have an Air Marshall on a handwritten family tree I received from my uncle about 20 years ago – and a family member I’d never heard of before at that. So I set to finding out more about it and thanks to the reliable online sources, have found out masses. But not some of the information in Hugh Halliday’s article. which was new to me.

Diana, this is a professional and highly informative coverage of the first Trans-Canada flight. Well done.

The vision those men had to plan an air crossing of Canada and the guts it took to actually do it are unbelievable. Your comment is a timely reminder, Jack, that I have promised readers Part 2, covering the second half from Winnipeg to Vancouver, flying DH-9 open cockpit aircraft in October!

I wonder if their experience in WWI prepared them for the trans-Canada flight. Leckie and Hobbs for instance had spent those years trundling over the North Sea in the fog and bad weather, so would be used to long monotonous flights, navigating with nothing more than a map, compass and spirit level, with several narrow escapes from death. It took its toll. At the beginning of 1918 a footnote in the Story of a North Sea Air Station by G F Snowden Gamble states “trips of 7 or 8 hours at a stretch seem to do a lot of pilots in, Hards, Galpin, Leckie being among many that have been permanently or temporarily knocked out from this action…. engine failure does not mean imprisonment, however disagreeable that may be, but starvation, frequently followed by death.” Not to mention drowning.

Your observations ring true, Susan. The early pilots were a hardy group, and that was clearly true of the men who flew the second half of the trans-Canada flight, crossing the Rockies through the Kicking Horse, Rogers, and Coquihalla passes. Please keep in touch as you pursue your discoveries. A/M Leckie made significant contributions to Canadian aviation, and I’m sure his name will be honoured as plans develop to mark the hundredth anniversary of the date when the Canadian Air Force officially became the Royal Canadian Air Force (1 April 1924.)

A great story, Diana – thanks so much for doing all the research necessary for this type of reporting. Mary Lou SImmons

Your father H.C.W. Smith might almost have been one of those pilots! His time in the Royal Flying Corps and Royal Air Force came at the end of the First World War and as far as I know he served only in Canada. Then of course he was one of the early HS-2L pilots in the Ontario Provincial Air Service, which built on the vision of the 1920 trans-Canada flight. Who knows what contributions he might have made to RAF Ferry Command in the 1940s if his life had not been cut short in 1941 by the crash in Scotland of Liberator AM261 returning to Canada. We will remember all the unsung heroes of Ferry Command lost during the war as we remember all who served tomorrow, on Remembrance Day.

Well done! As always, wonderfully written and impeccably researched! Looking forward to part two.

What I’m eagerly awaiting is your forthcoming history of RAF Ferry Command Gander Unit. Readers can look for North Atlantic Crossroads, by Darrell Hillier expected to appear in 2021. It will be a grand addition to Ferry Command and Gander literature.

Yet another detailed and thoroughly researched article Diana, a tip of the hat to you.

Thanks John! The courage and determination of all involved was truly remarkable.