During the Second World War, PBY Catalinas served the Allied forces well, mainly on coastal surveillance missions. Here, Catalina Z2147 (a Mark I Catalina), approaches the southern tip of Gibraltar after completing an anti-submarine patrol for RAF No. 202 Squadron. © IWM (CM 6524)

“The PBY* was involved in almost every major operation in World War II, and figured significantly in defeating the U-boat menace in the Atlantic.”

– U.S. Naval Aviation Museum, Pensacola, Florida

*PBY: PB stands for Patrol Bomber and Y indicates the manufacturer, Consolidated Aircraft, based on the U.S. Navy system of 1922.

The year was 1943 when my uncle Bruce Watt, a captain-navigator with the Royal Air Force (RAF) Ferry Command, flew three PBY Consolidated Catalinas or “Cats” from Bermuda to Scotland, in the months of February, May and November. These were among more than 500 PBYs that the Montréal-based ferry organization delivered from North American factories to the Allied Air Forces during the Second World War. [1]

All three Catalinas featured here were built for the RAF by Consolidated Aircraft in San Diego, California, under the 1941 Lend-Lease agreement between Britain and the United States. They would serve in operational and training roles protecting the coastlines of Allied nations and defending their shipping lanes against enemy submarines.

Consolidated Catalina IVA flying boat of the RCAF, Rockcliffe, ON, September 1941. Photo: National Defence/Library and Archives Canada/PA-064048.

The Catalina – known as a Canso in Canada – was ideal for this task because of its long range. It could cover a distance of just over 3,000 miles with a normal fuel load, and 4,000 miles when equipped with overload fuel tanks. With its parasol wing spanning 104 feet and its length of almost 64 feet, the twin-engine Cat was an imposing aircraft. The total wing area measured 1,400 square feet – nearly double the size of a post-war bungalow. All but 11 of the RAF Cats were non-amphibious “flying boats” that took off and landed on their hull. Wing floats provided stability on the water but once the Cat was airborne, the floats retracted to form streamlined wingtips. Centred below the huge single wing was a large pylon from which the hull was suspended. The hull itself was just over 10 feet wide, with a draught of less than 3 feet under a normal load. Two Pratt and Whitney twin-row 14-cylinder Wasp radial engines each delivered an output of 1,200 horsepower, giving a cruising speed of 117 miles per hour. The maximum allowable all-up weight was 35,420 pounds. [2]

For summertime deliveries, Ferry Command sent the Catalinas from Bermuda to Scotland via Gander, Newfoundland. In winter, the need for ice-free waters for takeoff and landing dictated the direct route from Bermuda. Even on the southern route, the flying boats often had to contend with an accumulation of ice as they passed through cold fronts. The extra fuel needed for the longer non-stop Atlantic crossing also posed a challenge in terms of added weight. From the earliest days, the senior people at Ferry Command worried about reduced safety margins: the weight of the overload fuel and tanks pushed the flying boats “beyond the maximum gross overload permissible on military operations.” [3]

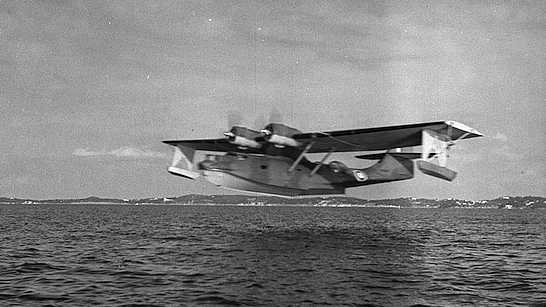

When departure time came, a heavily laden Catalina would dig its nose into the ocean, sending sheets of water up over the cockpit. With windscreen wipers going like mad, it would struggle at full throttle for as long as three minutes to get on the step, looking “more like a submarine than a flying machine.” Finally it would get unglued from the water, lumber into the air and make its slow climb to cruising altitude before heading off more than 3,000 miles on the “prodigious hop” to the United Kingdom. [4]

Consolidated Catalina I taking off from Bermuda to be ferried to Britain. Photo: A. Douglas Pearce / Library and Archives Canada / PA-092525.

Catalina FP316 – Watt’s First Catalina Delivery

In January 1943, Watt was assigned as captain on his first Catalina – a Catalina IB (constructor’s number 1009), with the RAF serial FP316. [5] He left Montréal by train on 8 January, heading for Elizabeth City, North Carolina. This was the receiving point for RAF Catalinas delivered from the manufacturer in California. On arrival at Elizabeth City, each aircraft would undergo an acceptance inspection by British officials. Any special equipment or upgrades would then be added. The aircraft would be given a flight test, have its compasses calibrated and its radio tested. Finally, it would be handed over to its ferry crew (pilot, co-pilot, navigator, flight engineer, and two radio operators) for the 6-hour trip to Bermuda.

One Catalina in full view near the beaching ramp at Darrell’s Island, Bermuda. In foreground, two Consolidated Coronados. Photo: Wing Commander E. M. Ware via Wikimedia Commons.

The Ferry Command post at Bermuda, on Darrell’s Island, had been opened in early January 1941 by Griffith “Taffy” Powell. As Bermuda base manager for Imperial Airways from 1937 to 1939, and a senior flying boat captain for the company, Powell had the knowledge and contacts needed to establish the staging base. Once the post was up and running, Powell was transferred to Montréal to become Operations Manager at Ferry Command’s new facility at Dorval airport where he served until 1945. [6]

Although the usual route from Elizabeth City led straight to Bermuda, Watt’s flight plan took him first to Nassau (another of Ferry Command’s en route stations) on 25 January 1943. He continued on to Bermuda with Catalina FP316 on 27 January – one of 18 arrivals that month from Elizabeth City. This date places him in Bermuda at the same time as Don McVicar whose book North Atlantic Cat is a must-read, chock full of adventure tales and fast-paced writing. He called the Bermuda-Scotland flight the toughest trip Ferry Command had to make. McVicar recounts how he set out twice from Bermuda in January 1943 only to be called back mid-ocean because of weather issues until on 5 February he finally made it all the way across. [7]

McVicar was not the only one delayed at Bermuda. Watt was also held up there, and landed an extra assignment as a result. When a special flight was needed at short notice, Watt and his crew were sent back to Elizabeth City with FP316 to pick up a load originally scheduled for Catalina W8430. A Catalina I, W8430 had been severely damaged on landing at Elizabeth City on 31 January. FP316 had no such problems, making a safe return to Bermuda with passengers and freight on 9 February. [8]

Watt would have to wait only a couple of days more to make the Atlantic crossing. He took off from Bermuda on 12 February and delivered Catalina FP316 on February 13. He was lucky. Departures could be held up for days by the wait for good tail winds and a reasonable weather forecast. Maintenance requirements further added to the delays. Ferry Command engineers in Bermuda had been kept busy in January dealing with autopilot issues on the Catalinas. Air to surface vessel (ASV) radar had also created problems. This brand-new airborne system for detecting ships at sea had been installed on all the new Catalinas. Unfortunately, its tree-like antennas attracted in-flight icing over the Atlantic, adding weight to the aircraft and slowing it down. Wisely, the powers-that-be soon ordered the antennas removed at Elizabeth City for transport inside the aircraft. [9]

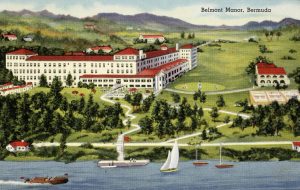

If you had to be delayed, Bermuda was not a bad place to be. Ferry Command civilian crews were billeted on the main island at the Belmont Manor, a pre-war luxury resort. Tennis courts, a golf course and a swimming pool offered a healthy option to the bar, and there was always the prospect of socializing with the young ladies working nearby in the British Government’s censorship office.

All such pastimes were set aside in the hours before departure. Rest was a high priority – if you were facing a risky flight averaging 22 hours and 30 minutes from Bermuda to Largs on the Firth of Clyde in Ayrshire, Scotland, you wanted to be on your best game.

At 5 in the morning, after an early breakfast, you would make your way down the steps of the Belmont, and head off to draw up your flight plan and attend a weather briefing. If the forecast was favourable, the tender launch would take you out to your mooring buoy. You would check the hull and the wing-tip floats, then climb in through the blister hatch. Once aboard, you would go through the standard pre-flight check of your aircraft, and run up the engines. This was the time to make sure that all cargo was properly stowed around the centre of gravity to avoid having your Cat behave like a dolphin, porpoising through the sea. At last the moment would come to cast off from the moorings and taxi into position for take-off from Bermuda’s Great Sound.

At 5 in the morning, after an early breakfast, you would make your way down the steps of the Belmont, and head off to draw up your flight plan and attend a weather briefing. If the forecast was favourable, the tender launch would take you out to your mooring buoy. You would check the hull and the wing-tip floats, then climb in through the blister hatch. Once aboard, you would go through the standard pre-flight check of your aircraft, and run up the engines. This was the time to make sure that all cargo was properly stowed around the centre of gravity to avoid having your Cat behave like a dolphin, porpoising through the sea. At last the moment would come to cast off from the moorings and taxi into position for take-off from Bermuda’s Great Sound.

Somewhere over the Atlantic, you would pass the point of no return. Once you crossed that line, you could only go forward – there was not enough fuel to go back. Through the long night, the tiny galley would offer the small luxury of coffee and hot soup to go with your sandwiches. Bunk beds were available, but there would be no real rest. Weather fronts or icing conditions had to be coped with, fuel and other gauges had to be monitored, and positions had to be checked by the moon and the stars or calculated by dead reckoning.

Meanwhile the pilot and co-pilot would spell one another, turning on the autopilot to give both men some relief. What was the Catalina like to fly? “Slow, prone to vibrate and heavy on the controls,” writes Roscoe Creed in his book PBY – The Catalina Flying Boat. “Not the most maneuverable plane in the air,” he adds. It was also very noisy, making those long hours over the Atlantic even more punishing. [10]

Eventually day would dawn, the coast of Ireland would be sighted to the south, and soon it would be time to land on the Firth of Clyde and make fast to a landing buoy in the lee of the island of Great Cumbrae. A launch would arrive to take you ashore to Largs on the mainland. Tired and hungry, you would be debriefed by the meteorologists so the latest information could benefit others, and then you would have the pleasure of your first proper meal since breakfast the day before.

Largs had become the receiving point for Catalinas in early 1943 after Scottish Aviation Ltd. determined this was a better location than its overcrowded facility at Greenock farther north at the mouth of the River Clyde. This company had the British government contract to install bomb racks, light armament and other equipment on the Catalinas to bring them up to RAF operational standards.

Largs had become the receiving point for Catalinas in early 1943 after Scottish Aviation Ltd. determined this was a better location than its overcrowded facility at Greenock farther north at the mouth of the River Clyde. This company had the British government contract to install bomb racks, light armament and other equipment on the Catalinas to bring them up to RAF operational standards.

Largs had many advantages over Greenock. It did not have the same strong tide nor the same congestion problems due to river traffic. The skies were free of industrial haze, and – more important – free of the barrage balloons used at Greenock against enemy aircraft. The journey to Prestwick or Ayr for passengers and freight was also shorter. By war’s end, Scottish Aviation had serviced more than 300 PBY Catalinas for the RAF at Largs. [11]

After delivery by Watt on 13 February, FP316 was allocated to RAF No. 202 Squadron, whose Catalinas were patrolling approaches to the Straits of Gibraltar from both the Atlantic and the Mediterranean. U-boat activity had greatly increased in February 1943, and the Squadron had made six attacks, one of which scored a kill. The allocation of a fresh-from-the-factory Catalina was no doubt most welcome. [12]

Having made his delivery, Watt had to wait for a flight back to Canada. Anxiety must have been high among those on the waiting list. Two of the Liberators in the Return Ferry Service operated by BOAC (the British Overseas Airways Corporation) for Ferry Command had set out from Ayr, Scotland, a few days earlier, on 8 February, but only one had landed safely – at Sydney, Nova Scotia. Both had encountered unexpectedly fierce headwinds, and AL591, without enough fuel to divert, had crashed near Gander. Nineteen lives were lost. Watt and his fellow travellers fared better, making it home safely to Montréal via Reykjavik on 2 March aboard Liberator AL627. Watt’s round trip had taken nearly eight weeks. [13]

Consolidated Liberator AL627 of the Ferry Command Unit of RAF Transport Command flying over Montréal, nearing the end of a flight from Prestwick, May 1944. Photo: RAF official photographer © IWM TR 2493.

Ferry Command Becomes No. 45 Group

Meanwhile, major organizational changes were in the offing for Ferry Command. In response to the pressures of wartime transportation, the RAF created a new command – Transport Command – effective 11 April 1943. Air Chief Marshal Sir Frederick Bowhill, who had been the top man at Ferry Command, was named to head the new command, responsible for all transport operations including ferrying. The former Ferry Command became No. 45 Group within Transport Command. Reginald Marix, formerly second-in-command to Bowhill at Ferry Command, was put in charge of 45 Group, with the rank of Air Vice Marshal. Air Commodore Griffith Powell, as Senior Air Staff Officer, was in charge of the operations side, including all flying personnel and flying training, as well as signals, engineering, traffic and meteorology. This was to be the final transformation of Ferry Command. [14]

The new name may have been “45 Group” but as Carl Christie notes in Ocean Bridge, it was always “Ferry Command” to members of the organization regardless of the period or the reporting structure. [15]

A Smooth Second Delivery – Catalina JX226

Catalina Mark I, Z2417, of RAF No. 202 Squadron flies by the North Front of the Rock as it leaves Gibraltar on a patrol. © IWM (CM 6238)

For his next Catalina crossing, Watt again travelled to Elizabeth City by train, the usual Ferry Command procedure, arriving there on 11 May. His delivery schedule was exceptionally smooth this time.

Watt flew a Catalina IVA – JX226 (constructor’s number 1249) – to Bermuda on 13 May, left Bermuda for Gander on 16 May, and reached Largs on 17 May after less than 15 hours in the air. On 20 May, he was already on his way home from Prestwick on a direct flight to Dorval aboard Liberator AM263. The return trip of nearly 16 hours, with Captain Buxton at the controls of the Liberator, took longer than the Catalina crossing from Bermuda. [16] Of course, the westbound flights normally had to fight headwinds that slowed their passage.

The 11-day turn-around time was surely one of the better records established at Ferry Command. In The Flying Boats of Bermuda, Colin Pomeroy notes that ideal flying conditions prevailed in May, allowing a total of 24 Catalinas to be delivered, the first 4 taking the direct route to the UK and the remaining 20 going via Gander Lake, as Watt did. [17]

Like FP316, Catalina JX226 was allocated to RAF No. 202 Squadron, to patrol the eastern and western approaches to the Straits of Gibraltar. It was subsequently reallocated to No. 131 (Coastal) Operational Training Unit at Killadeas in Northern Ireland. [18]

Bruce Watt’s Third Catalina – JX251

The third and final Catalina delivered by Bruce Watt – JX251 (constructor’s number 1446) – was a model IVA like JX226. This time, Watt went by air to Elizabeth City as a passenger in Dakota FL530, arriving 21 October 1943. Delays held him up for a week there before he could make the trip to Bermuda with JX251. It was another week later when he took off from the Great Sound on November 4, flying the direct route across the Atlantic to reach Largs on 5 November. This was one of ten Catalina deliveries by Ferry Command in the month of November. [19]

Watt arrived back in Montréal on 21 November. His final Catalina delivery had taken a full month from start to finish – quite a contrast to the 11 day total for JX226, but far better than the 53 days for FP316.

After the usual upgrading work by Scottish Aviation, JX251 was allocated to No.131 (Coastal) Operational Training Unit in Northern Ireland, joining the fleet used to train crews to fly on the Catalina. [20]

Watt was spared the strong winds experienced in Bermuda in mid-October 1943. Usually when storms hit the island, the Catalinas were brought ashore on their wheeled beaching dollies and tied down on the paved work aprons. But sometimes, as on this occasion, crews were asked to stay on board their flying boats at their moorings to maintain an anchor watch in the rough seas and to run the engines as needed to ease strain on their mooring lines. McVicar had the experience of riding out a Bermuda gale aboard a moored Catalina in December 1942, which he describes in North Atlantic Cat. [21]

Return to Dorval via Trans-Canada Air Lines

After completing his delivery on 5 November, Watt returned to Montréal via the Canadian Government Trans-Atlantic Air Service. Terry Judge, an Ottawa-based aviation researcher, kindly shared some details about the service and this particular flight. Inaugurated in July 1943, the CGTAS had a mission to provide a priority freight, mail and VIP passenger air link with Britain to support Canada’s wartime efforts. Watt was one of four passengers aboard the converted Lancaster bomber CF-CMS when it left Prestwick on November 18 at 0914 GMT under the command of Captain Lindsay Rood, making its seventh westbound flight. [22]

Avro Lancaster Mark I CF-CMS, operated by Trans-Canada Air Lines for the Canadian Government Trans-Atlantic Air Service. Photo: Canada Aviation and Space Museum, KM2291.

The flight arrived at Meeks Field, Iceland, at 1411 (all times GMT), only to be held up there for two days. On 20 November at 1400 the Lancaster departed from Iceland, reaching Gander at 2355. After an overnight stop, it took off from Gander on 21 November at 1228 and finally landed at Dorval at 1700. The actual flying time spread over four days was 18 hours, 24 minutes.

CF-CMS was the first of a fleet of nine Lancasters (the other eight were transport versions of the Canadian-built Lancaster X), and the only one in service at this time. On this trip, it left Prestwick with 4,424 pounds of mail and 195 pounds of cargo in addition to the 4 passengers. At Meeks Field, it picked up an additional passenger, and an extra 369 pounds of mail were loaded at Gander.

This was the beginning of a new era in Canada’s aviation industry. By 1944, the CGTAS was well established, operating on a three-times-a-week schedule between Canada and the UK. In the course of the year, the service carried 2,000 passengers and one million pounds of mail, and helped lay the foundation for Canada’s role in post-war international air transport. [23]

Published 15 March 2018. Revised 18 March 2018.

Acknowledgements

Many people helped me as I was researching and writing this post. Sincere thanks to the following, who are in no way responsible for any errors of fact or interpretation. If you spot an error, please contact me so that it can be corrected!

For research assistance and contributions, my thanks to Sylvie Bertrand of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum; André Durocher; George Fuller; Darrell Hillier; Mathias Joost; Terry Judge; Ian Macdonald; and Bob Smith. Thanks also to John Davidson for editing the maps I prepared for use here.

Finally, several readers offered comments which helped to shape the final version of this post: Blanche Conder; John Crook; André Durocher; Janice Kelly; and Ian Macdonald.

Footnotes

See Sources, below, for full references to the authors cited.

[1] Christie, p.12, and Powell, p. 80.

[2] Pomeroy, p. 178. Creed, p. 307, lists the 11 RAF amphibious Catalinas (Mark PBY-5A) produced under contract 88476 and delivered in 1942.

[3] C. H. “Punch” Dickins, vice-chairman, Air Services Department, Canadian Pacific Railway Company, letter of 15 March 1941, to Air Vice-Marshal L.S. Breadner, Chief of the Air Staff, Royal Canadian Air Force. Library and Archives Canada, RG 24 vol. 5240, “Royal Air Force Ferry Command: Aerodromes and Facilities for – Organization,” HQ S19-55-1- vol. 1. See also Pomeroy, p. 83-88, for RAF Warrant Officer pilot Reg Baynham’s account of the delivery of Catalina JX215. Baynham notes how low the aircraft sat in the water at Bermuda and remarks that she was some 5,000 pounds overweight.

[4] See Powell, Ferryman, p. 31, and Per Ardua Ad Astra: A Story of the Atlantic Air Ferry (n.p.).

[5] FP316 was one of 75 RAF Catalina IBs manufactured under contract 88477-DA, while JX226 and JX251 were among 70 Catalina IVAs produced under contract 91876-DA. Creed, p. 307.

[6] Christie, p. 104. At his own request, Powell reverted to civilian status to facilitate dealings with senior officials during his stint in Bermuda. Memo from RCAF Squadron Leader G.J. Powell to The Secretary, Department of National Defence, 28 December 1940. Library and Archives Canada, RG24 5240, HQ S-19-55-4, “RAF Ferry Command, Posting of RCAF Personnel to.”

[7] McVicar, p. 40.

[8] Pomeroy, pp. 64, 67, 226. Catalina W8430 water looped on landing and suffered extensive damage. Major servicing and repairs were carried out at the U.S. Naval Operating base in Bermuda in June 1943. The aircraft crashed at Bermuda on 7 October 1944.

[9] Pomeroy, p.63, and McVicar, pp. 67-68, 93.

[10] Creed, p. 2.

[11] Berry, from https://forum.keypublishing.com/showthread.php?79958-Scottish-Aviation-Ltd-Largs-Seaplane-Terminal Post of 8 April 2008. Accessed 6 January 2018. My assumption that Watt delivered all three Catalinas to Largs is based on Pomeroy’s summaries of Bermuda base activities (p. 63 ff.). The crew cards merely show the destination as “UK”.

[12] Creed, pp. 249-250.

[13] McVicar, pp. 106-113. Christie lists the deceased on p. 317.

[14] Marix, speech to the Empire Club.

[15] Christie, p. 195.

[16] JX226 left Gander at 2310 May 16 and arrived at Largs at 1350 May 17. AM263 departed Prestwick at 2001 May 20, reaching Dorval at 1156 May 21. All times GMT. From the Gander Log, courtesy of Darrell Hillier.

[17] Pomeroy, pp. 66.

[18] Creed, pp. 249-50 and RAFWEB.

[19] Pomeroy, p. 70. From the end of October, deliveries were sent direct from Bermuda to the UK.

[20] RAFWEB.

[21] Pomeroy, p. 70. See also McVicar, pp. 59-61 for his experience riding out a gale in a Catalina.

[22] Terry Judge, Personal communication (by email,) 17 November 2016.

[23] Christie, Chapter 12, “Lasting Legacy,” especially p. 290.

Sources and suggested links

202 Squadron Association website: http://www.202-sqn-assoc.co.uk/ Accessed 14 March 2018.

Berry, Peter. Prestwick Airport & Scottish Aviation. Stroud, Gloucestershire, U.K.: Tempus, 2005.

Christie. Carl A. Ocean Bridge: The History of RAF Ferry Command. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1995.

Creed, Roscoe. PBY – The Catalina Flying Boat. Annapolis, Maryland, U.S.A.: Naval Institute Press, 1985.

Canadian Armed Forces, Directorate of History and Heritage, “RAF Ferry Command Crew Cards,” DHist 84/44.

Flight magazine, 1 February 1945, pp. 118-9, 120-1, “The Lancastrian.”

Legg, David. Consolidated PBY Catalina: The Peacetime Record. Annapolis, Maryland, U.S.A.: Naval Institute Press, 2002.

Marix, Air Vice-Marshal Reginald L.G., “Some Aspects of the Royal Air Force Transport Command,” The Empire Club of Canada Addresses (Toronto, Canada), 4 November 1943. http://speeches.empireclub.org/62592/data Accessed 14 March 2018.

McClellan, J. Mac. “Consolidated’s PBY-5 Catalina,” 5 March 2007. https://www.flyingmag.com/pilot-reports/pistons/consolidateds-pby-5-catalina Accessed 15 January 2018.

McVicar, Don. North Atlantic Cat. Shrewsbury, England: Airlife Publishing, 1983.

Pomeroy, Colin A. The Flying Boats of Bermuda. Bermuda: Printlink, 2000.

Powell, Griffith. Ferryman: From Ferry Command to Silver City. Shrewsbury, England: Airlife, 1982.

–– Per ardua ad astra: A Story of the Atlantic Air Ferry, Montréal, 1945. Copies distributed to 500 civilian air crew.

[Pudney, John.] Atlantic Bridge: The Official Account of R.A.F. Transport Command’s Ocean Ferry. Prepared for the Air Ministry by the Ministry of Information, 1945. Honolulu: University Press of the Pacific, 2005. Reprinted from the 1945 edition.

U.S. Naval Aviation Museum, Pensacola, Florida http://www.navalaviationmuseum.org/attractions/aircraft-exhibits/item/?item=pby-5a_catalina Accessed 14 March 2018.

Wikipedia, “Consolidated PBY Catalina,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Consolidated_PBY_Catalina Accessed 14 March 2018.

–– “Avro Lancastrian,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Avro_Lancastrian Accessed 14 March 2018.

RAFWEB. www.rafweb.org Accessed 14 March 2018.

[end]

Hello Diana,

I’m not sure if I’m doing this correctly as I’m not very good with computers and never tried replying to a “link”!

The link was forwarded to me by Margy Duncan whose father was a meteorologist with the RAF in Bermuda (I think you have been in touch with her brother) and Margy thought you would like this information.

My father, Ray “Lofty” Davis, was posted to 131 OTU, Killadeas in May and June 1944 and flew JX251 on three occasions. Firstly on 23rd May where his log book states: 1hr dual; 1;45hr 1st pilot and 2;40hr 2nd pilot – there is nothing recorded under “duty” for that sortie.

He next flew it on 6th June for 3;35hr as 1st pilot – duty recorded as “OFEI”

He flew it on the last occasion on 9th June for 50min dual and 3:00hr 1st pilot – duty recorded as “14-22-27-28”

I hope this is of interest to you.

All the best,

Peter Davis

This really rounds out the story of Catalina JX251 once it reached RAF Killadeas on Lough Erne. Perhaps some other reader will be able to enlighten us about the notation “OFEI” or the June 9 log entry “14-22-27-28”.

What did “Lofty” Davis do in the RAF after completing his training on the Catalina? There are so many stories behind the stories!

I’ve only just discovered this wonderfully written piece in doing some research on PBY Catalinas in Bermuda. Long story short my late father travelled from Aberdeen in Scotland to Bermuda via Elizabeth City in May 1943 with the RAF. Based there as a meteorologist and met my late mother the daughter of the Belmont Manor manager. The potential coincidences of the time this was recorded to perhaps that same flight and potentially delivering the weather briefing etc etc

What a coincidence that would be, if my uncle Bruce Watt was pilot on a Catalina carrying your father from Elizabeth City to Bermuda. We must compare dates. I see from Pomeroy’s book The Flying Boats of Bermuda that W/C Ware, commanding officer of the RAF base at Darrell’s Island, Bermuda, also made a special flight from Elizabeth City to Bermuda during May 1943 in Catalina trainer V9712 (specific date not given). Would love to hear more of your father’s story.

Diana, what a fantastic article, your research is wonderful.

My father flew Catalinas from Pensacola, and I’d love to try and find out anything at all about his journeys and who he flew with. His name was Andrew Strachan.

Can you point in the right direction of where to start with my research?

In September 2018, I visited Largs in Scotland so I could see where Uncle Bruce landed the Catalinas he delivered and where Scottish Aviation had its workshops to fit upgrades and armaments on the Cats as they were delivered. Will post about this sometime soon.

Meanwhile, I’ll be glad to see how I can help you get started on your research, and will contact you privately about that.

Research is fun, but the greatest rewards are in sharing the findings and encouraging others with similar interests.

My father ferried two cats over, the first was after training with US navy at Pensecola

Richard, can you tell us more about your father? Was he a captain in the RAF Ferry Command? When did he make these ferry flights? Did he land at Largs, Scotland? What other aircraft did he deliver during the war years?

I’m glad you mentioned the Pensacola Naval air station. I don’t know whether or not Uncle Bruce had any training there. Just one of the many things I have yet to learn about him. Looking forward to hearing more about your father.

Great article, my father was an RAF navigator with Ferry Command based in Montreal and I remember him telling me that when Catalinas headed for the UK the pilots would reduce power to the point where he said that you could practically see the propeller blades as they spun.

His name was William George Franklin and his name appears several times in the book Ferryman unfortunately his name is shown as William F Franklin.

That old saying that safe pilots get to be old pilots must be true. Reducing power saved on fuel and increased the safety margin, though at the cost of reduced speed. One Ferry Command delivery Catalina was in the air for a little more than 30 hours – its tanks must have been dry when it put down!

Bill Franklin was a highly valued member of Ferry Command, according to Powell’s Ferryman book, because of his skills as a navigation specialist. Impressive too that he followed Powell into British Aviation Services and then Silver City as his right hand man before joining Aer Lingus. All facts that I learned only because of your comment.

Did he write about his career himself? Or have you perhaps written about his life in aviation?

Thanks for getting in touch, and please write back with more about your father –

Diana

Diana, I very much enjoyed your article about ferrying RAF Catalinas through Darrell’s Island in Bermuda. There is a Canadian connection to the RAF Catalinas and Bermuda.

Douglas, p.386 and Pomeroy, p.57 report that as early as May 1940 the Permanent Joint Defence Board had recommended that the RCAF be equipped with Consolidated PBY Catalina flying boats to prepare for the inevitable extension of German U-boat operations into the western Atlantic. By May 1941, the RCAF had not received any of their PBYs on order from Consolidated or Boeing Canada and the UK Air Ministry was very reluctant to loan the RCAF any PBYs destined for the RAF because of the pressing U-boat action in the western approaches to the UK. It was not until May 1941 when German U-boat transmissions placed a U-boat at 55N 50W, just barely in reach of RCAF Digbys based in Gander, but well within range of Catalinas, that the situation became critical.

This broke the bureaucratic log jam and the Air Ministry informed the RCAF that nine Catalinas destined for the RAF in Bermuda were being diverted to Eastern Air Command. The Catalinas were loaned subject to replacement from the delivery of Catalinas from the RCAF’s own orders. Crews from 5 Bomber Reconnaissance Squadron at RCAF Station Dartmouth were sent to Bermuda for training and the first Catalinas arrived at Dartmouth in June 1941. The squadron was considerably shaken when orders arrived to transfer the experienced personnel and all Catalinas to 116 (BR). 116 (BR) immediately sent a detachment of four Catalinas to Botwood NL to escort convoys through the Straits of Belle Isle. 5 (BR) Squadron reverted to their Stranraers at Dartmouth for convoy escort patrols south of Nova Scotia.

I’m honoured to welcome you as a reader. Thanks for extending the story to include the role of Catalinas in Eastern Air Command during the Second World War.

Diana

(Ernie Cable retired as a Colonel from the RCAF in 1995 after 35 years of service mostly in maritime patrol on the East coast. He was with the Shearwater Aviation Museum in Nova Scotia as its historian, and has since become an Associate Air Force Historian. The Douglas book he mentions is: W.A.B. Douglas, The Creation of a National Air Force.)

Congratulations Diana!! Another informative and inclusive article on your aviator Uncle and details of his historic flights.

I look forward to your next research!!

Thanks for the support, Jeannie!

Do you have the names of the other crew members on the three flights? It would be good to give them credit and backgrounds.

Did the delivery flights fly solo or as a group of aircraft?

Were there any losses of Catalinas during the ferry trips?

Do you have any records of what finally happened to the three Catalinas which he flew? Did they make it through the War, possibly into into post war civilian service of some type?

Response to J Crook comments

John,

These are all really good questions.

1. As you say, it would be appropriate to credit the entire crew on these flights but I don’t have that information. The Ferry Command crew assignment cards held by the Directorate of History and Heritage of the Canadian Armed Forces tell me what aircraft Bruce Watt flew, where he went and the dates. For the early flights through Gander (1940-41), the Gander log noted all crew and passengers. As the delivery pace increased, the record keeping was reduced to the bare minimum. As for going through all the cards to find a match – well, there are some 10,000 cards altogether.

2. Ferry Command flights were essentially solo. Group formations were used only for the four flights of Hudsons in 1940. Adopted because of a shortage of navigators, the plan proved unworkable in the winter weather conditions of the North Atlantic. However, dispatchers often sent several aircraft off to the same destination within a fairly short time period, primarily to meet delivery needs. For example when Bruce Watt took off for Largs from Gander Lake on May 16, he was following Catalinas JX222 and JX222 and was followed by Catalina JX224. The separations in this case ranged from 30 to 120 minutes.

3. A few Catalinas were lost during ferry trips. In Ocean Bridge, Appendix B, Christie lists seven Catalinas lost (only two crew members survived). One of the best known losses was that of Catalina FP116 in March 1943. Captain “Duke” Schiller, legendary Canadian bush pilot, crashed in a glassy waster landing at Bermuda, having been forced back by engine problems. Christie’s list includes the crash of Catalina 02915 in January 1945 during a night take-off from Elizabeth City, N.C. However, the serial number suggests this aircraft, destined for delivery to the Soviet Union, was a PBN-1, a Nomad. If so, the list should also include a PBN-1 lost in June 1944 on delivery between Reykjavik and Murmansk, USSR. That would bring the list of losses to eight.

Pomeroy, pp. 223-28, adds to the above, for a total of ten losses. On 11 December 1942, Catalina FP315 having negotiated a severe weather front while on delivery then had to make an emergency landing east of Gibraltar alongside an RN destroyer. It sank while being towed. On 7 April 1943, Catalina FP138 was heading for Largs but was redirected to Mount Batten near Plymouth due to strong winds. It went off course, landing near the coast of occupied France. Two crew died trying to swim ashore; the captain and other crew became prisoners of war.

4. Creed, p. 283, says that the Catalinas were rapidly retired from service when the war ended. Under the Lend-Lease agreement, surviving aircraft were to be returned to the United States but the country had more than enough surplus planes on hand. In fact, nearly all the RAF Catalinas were reduced to scrap by March 1947. No doubt this fate befell the three delivered by Bruce Watt. (Creed’s source for this is the U.K. Air Ministry paper AM.3/77, “The Consolidated Catalina in Royal Air Force Service.”)

I hope this answers your queries, John. I’m always amazed how much detail can be found – and how hard it is to fit everything into a post!

Diana