If you receive this post via email, try reading it here on the internet.

Waterfowl flapped madly as they rose from the water to escape the massive bird that splashed down among them, darkening the sky with its 74-foot (22.5 m) wingspan. A Curtiss HS-2L flying boat had taken refuge from engine trouble at Rivière-aux-Canards, on the south-west coast of Anticosti Island, Québec. The roar of its 360-hp Liberty 12-cylinder pusher engine only added to the avian panic that August day in 1922.

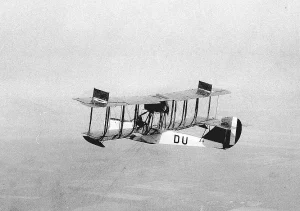

Curtiss HS-2L flying boat G-CYDT at Victoria Beach, Manitoba, 1921. Credit: Canada. Dept. of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / PA-053283.

Anticosti had just welcomed its first visiting aircraft – a flying boat on a mission tied to government policies.

After World War 1, Canada was eager to promote civil aviation as a tool of economic development. Officials targeted forestry as a top priority. Airborne surveys could revolutionize the industry by speeding up mapping of timber types and assessment of their commercial value.

Québec Forests Worth $600 Million in 1922

Forestry was a key industry in Québec. Its softwood and hardwood stands had an estimated market value of more than $600 million according to the May 1922 issue of Illustrated Canadian Forestry magazine.

The province needed an inventory of its forest resources. For its part, the federal government wanted to demonstrate the benefits of aviation. In 1920, they started a co-operative program at Roberval, on Lac Saint-Jean, 257 km (160 mi.) north of Québec city. The province provided the site and structures for an air station, while the Canadian Air Board supplied both personnel and seaplanes – Curtiss HS-2L flying boats that had been used by the Americans for coastal submarine patrols in World War 1.

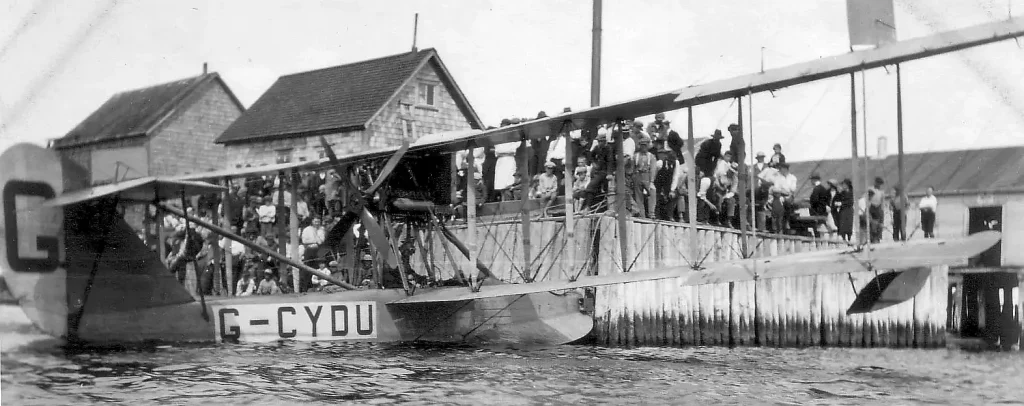

Curtiss HS-2L G-CYDU at Richmond, B.C. Credit: City of Vancouver Archives. Photo: Maj. J.S. Matthews.

At first, the project focussed on areas north and west of Roberval. In Summer 1922, two HS-2Ls (H-boats) flew surveys while a third transported men and supplies to a remote base camp. As Fall approached, Québec’s attention turned to the North Shore of the St. Lawrence River. Provincial officials requested a fourth aircraft to fly aerial surveys in parallel with a traditional ground survey crew operating from their base at Natashquan.

An H-boat at the Halifax air station in Nova Scotia fit the bill. G-CYDU had been assembled – “erected” as they said then – and licensed in 1921. The pilot and crew assigned to the airborne survey hurried to Halifax, taking the train from Roberval. On August 17, they left for Natashquan … but CYDU never reached the North Shore.

Crowds gathered to greet the Curtiss HS-2L flying boat G-CYDU at Richibucto, N.B. Credit: Virginia MacKinnon, Richibucto Photo, courtesy of Harold Skaarup.

Emergency Landing at Anticosti Island

All began well. CYDU headed north to Richibucto, New Brunswick, where enthusiastic crowds welcomed her. She then tracked north via Gaspé, Québec, towards Anticosti. But ten minutes short of the island’s main village, Port-Menier, the engine faltered. [1]

At 6 p.m., August 17, a message alerted Anticosti manager Georges Martin-Zédé that a flying-boat had passed La Loutre river, flying very low and heading towards Ellis Bay, Port-Menier’s harbour. [2] Soon afterwards, a second message reported the airplane passing the next river, the Sainte-Marie. Then silence.

Martin-Zédé waited expectantly at the harbour – but CYDU was a no-show.

An overheated radiator had forced the pilot, Flight Lieutenant W. R. Kenny, DFC, air station superintendent at Roberval, to land among the ducks and geese at Rivière-aux-Canards. One of the men on board was an aircraft mechanic – in those days airplanes seldom travelled without one. Air engineer A. E. Wright set to work at once and struggled with the fouled radiator until sunset. [3]

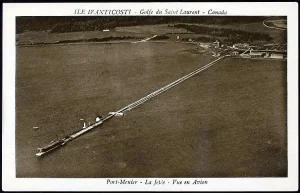

Success came only the next morning. At 9 a.m. on August 18, CYDU finally landed at Ellis Bay and taxied over to Anticosti’s long jetty – easy to spot at more than half a mile (1 km) in length. [4] On hand to greet the airmen, Martin-Zédé extended a warm welcome.

Grounded, they spent the whole day working on the radiator. That night, a storm brought driving rain and a cold south-east wind. You can bet they were grateful for warm beds and a roof over their heads.

August 19 saw three of the four marooned men using their expertise to help Martin-Zédé with Anticosti’s new wireless system while Wright struggled on with the radiator. To no avail. Both test flights on August 20 failed: that darned radiator kept overheating. On August 21, they threw in their cards. They simply could not trust CYDU to fly the last 160 km (100 mi.) across the open waters of the Gulf of St. Lawrence to Natashquan let alone complete the survey flights.

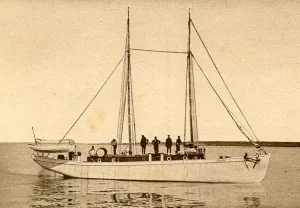

Ever helpful, Martin-Zédé came to the rescue. On August 22, he dispatched the Anticosti Vedette to take the would-be aviators to Gaspé. From there they would return to Roberval and regroup.

CYDU would stay put. The Air Board would deal with her when time permitted.

Another aircraft still had to be found for the North Shore survey. Luckily, one was at hand. A week earlier, Major A. B. Shearer, superintendent of the air station at Halifax, had delivered HS-2L G-CYEK to Roberval. [5]

G-CYEK, the second aircraft at Anticosti

Pressed into service, CYEK left Roberval for Natashquan on 31 August 1922. At the controls again, Kenny followed the Saguenay River south to Tadoussac, then hugged Québec’s North Shore until he neared Anticosti. Crossing the St. Lawrence to Port-Menier on September 1, he spent the night there and crossed back to Natashquan the next day to team up with the ground survey party.

CYEK thus became the second aircraft to visit Anticosti Island.

Martin-Zédé and Kenny, both decorated veterans of World War 1, had a clear vision of the many benefits aviation could bring to Anticosti. Over lunch before Kenny’s departure, they talked at length about a possible future role for Ellis Bay as an aviation centre. [6]

G-CYDU heads home

Meanwhile, CYDU had to get back to Halifax. Shearer and a mechanic travelled by train from Halifax to Québec City, then took the river steamer North Shore to Anticosti. It was September 14 when they reached Port-Menier.

They immediately got to work on the Liberty V-12 engine while G-CYDU rested at her moorings on Lac Plantin. This freshwater lake near Port-Menier would later become host to many other seaplanes visiting Anticosti. [7]

Martin-Zédé stopped by to invite Shearer to join him for lunch the next day. Once again, conversation turned to the role aviation could play in Anticosti’s future. Air service could mean regular delivery of supplies and mail the whole year round, improve monitoring of forest fires and poaching activities, and simplify transportation of fishing and hunting guests. Shearer himself spent two happy days checking out Anticosti’s deer and bird hunting by special invitation. [8]

Finally CYDU was ready for the flight home to Halifax. Martin-Zédé’s diary records that Shearer and his mechanic took off at 10 a.m., September 22, and landed at Halifax the next evening “après un bon voyage.” But the facts suggest that in reality the return flight was a harrowing experience.

CYDU had developed a weight problem. Her tare weight skyrocketed as her hull soaked up countless gallons of water during her five weeks’ exposure to the elements at Anticosti. This put her well above the approved empty weight for an H-boat of 4,300 pounds (1,950 kg).

Not only that but the HS-2L design was far from being aerodynamic. Lieutenant-Colonel R. Leckie, Flying Operations Superintendent at the Air Board, criticized the design in a 1920 report. He singled out the flying boat’s head resistance, noting that it was “very high owing to the lack of streamlining of hull, struts, etc.” [9]

Fearful the Liberty V-12 engine would overheat once again from confronting the heavy winds and the many other stress factors, Shearer flew close to the water for the entire trip. His strategy allowed for a quick landing in case the radiator misbehaved, blowing its cap and possibly showering him with scalding water.

Even without this threat, flying an H-boat was no picnic. U.S. Coast Guard aviation pioneer William Wishar found the HS-2Ls had to be “constantly ‘flown’ while in the air.” You could also end up lame after a flight, he griped, from all the non-stop right-foot pressure needed on the rudder-bar pedal to offset the torque of the H-boat’s four-bladed propeller. [10]

Shearer coped with all the challenges, including the after-effects of the war wound he had taken in his thigh. Flying cautiously, he took 11½ hours to complete the trip back to Halifax – almost twice the normal time according to the Halifax Evening Mail of 27 September 1922. After an overnight stop at Campbellton, N.B., to recover and refuel, he reached Halifax exhausted but safe – and CYDU’s adventure ended well.

G-CYEK – Damaged Beyond Repair

G-CYEK had no such luck. With the aerial portion of the Natashquan survey completed, Kenny left Sept-Îles on 21 September 1922, flying west along Québec’s North Shore. He landed on the Godbout River to top up CYEK’s fuel reservoir from cans of gas he had stowed on board. This way he could be sure of the quality of the gas the aircraft would be using.

After refuelling, he taxied downstream preparing to take off. But there were unexpected hazards. CYEK passed safely under a telegraph line that crossed the river. A second wire, a telephone line strung across the river at a height of four feet (1.2 m), cut into the hull of the flying boat and snapped apart. They checked for damage to the hull but found nothing of concern.

Kenny abandoned the river in favour of the open waters of the Gulf of St. Lawrence. There he would have where he would have unimpeded space for the long run CYEK needed to get airborne. A bad choice, as fate would have it.

Anticosti Island and the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

Kenny got more than he bargained for. Heavy waves pounded the H-boat relentlessly. CYEK was only semi-airborne, careening from the crest of one wave to the next. Soon water gushed up through the floorboards.

Then came the final blow. A huge wave broke over the front cockpit. CYEK nosed over and began to sink, with the engine sticking up behind. Kenny frantically throttled back and switched off the engine, then scrambled up through the 800 pounds of high tensile steel flying wires strung between the wings. Vastly relieved, he discovered his two passengers already safely perched on top. [11, 12]

Many reports claim that CYEK sank off Anticosti. Not so. The Court of Inquiry report clearly shows that the mishap occurred close enough to Godbout for residents to launch their motorboats, rescue those on board, and tow the flying boat as close to shore as they could, given the high wind and strong current.

Kenny and Wright retrieved the photographic equipment, negatives and notes, while Wright salvaged the engine. The hull was sacrificed as beyond repair. The humans fared somewhat better. Méthot suffered a cut on his eyelid, and Kenny came down with a very bad cold, not improved by dunking in the frigid waters of the Gulf of St. Lawrence (September average 8.5°C or 47.3°F). [13]

Rave Reviews from Québec

Québec was delighted with the season’s work. In a glowing report, provincial forestry engineer Alphonse Landry praised the work done by the Roberval station.

The use of aircraft in 1922 enabled his department to take 2,225 vertical photographs and sketch timber types in more than 2,100 square miles (5,440 km²) of territory in the Roberval area. In the Natashquan valley, in just 40 hours of flying time, they completed aerial reconnaissance and forest sketching over an area of 3,145 square miles (8,145 km²).

Overall, Landry concluded, the project dramatically showed what a valuable contribution aviation could make in the forestry sector. Sweet music to the ears of everyone at the Air Board! [14]

The Backstory

The starting point for this story was Luc Jobin’s interview with Arthur Renaud recorded on January 12, 1975. Renaud lived on Anticosti Island from 1919 to 1929, serving as chief accountant for the Menier family and later for the Anticosti Corporation. In the interview, he recalled the first aircraft that came to Anticosti:

“The first plane here was a flying boat that landed on Ellis Bay in 1922,” he told Jobin. “It had been chartered by the Québec Department of Lands and Forests, and arrived from Gaspé. En route it had to make an emergency landing at Rivière-aux-Canards.”

When the engine repairs were completed, Renaud recalled, he was invited to ride along on the test flight – his thanks for providing receipts allowing the flyers to claim expenses for their stay at Anticosti Island when they had actually been the guests of French multi-millionaire Gaston Menier, the island’s owner and member of the Menier dynasty of chocolatiers.

Jobin first travelled to Anticosti in 1972 for his work as a forest entomologist. Enamoured with the place and its people, he soon found a second career as an expert on the history of the island and its families. His oral history Entretiens avec des anticostiens,1975-1981 can be found online at https://www.comettant.com/entretiens-anticostiens-jobin/sujets-des-entretiens/ It is now also available in book form: Anticosti m’est racontée / Luc Jobin [published at Bromont, Québec, by the author in 2021].

The backstory blossomed with the realization that the diaries of Georges Martin-Zédé had been digitized by the Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (BAnQ) and could be consulted online. Martin-Zédé managed Anticosti for the Menier family, owners of the island since 1895. He spent the winter months in France, but from May to October he lived at Port-Menier, Anticosti. His diaries are a goldmine of information, noting the dates and details of daily events for 27 years (1896-1929). This article relies on his 1922 journal.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Information and advice has come from many people. First and foremost, the late Ron Dixon generously shared background on Anticosti Island and drew my attention to key sources. Ron was manager of Anticosti Island for Consolidated Bathurst Ltd. for many years. When he and his wife Lise moved to Montréal after he retired, he became a stalwart member of the Montréal Chapter, Canadian Aviation Historical Society, where I met him. His passing on 1 January 2021 was a great loss.

Alastair Reeves has engaged in numerous conversations – always enlightening – about forestry management, the early use of aircraft in Québec for fire patrols and forest sketching, and the unique characteristics of the Curtiss HS-2L flying boats. Years of experience in silviculture with the British Columbia Ministry of Forestry, his academic studies and his personal research interests give him a rare depth of knowledge on the subject. His advice and guidance have been invaluable.

John Orr and Hedley Auld, members of the informal Aerial Research Collective, have kindly shared pertinent documents from their extensive research on the Canadian Air Board 1920-1923. They have filled in numerous details about the Roberval air station and provided a context for government aviation policies and programs of the day.

Others who offered helpful research assistance were Paul Durand, Canadian War Museum, and Pierre Verhelst, volunteer historian and founding member of The Canadian Bushplane Heritage Centre at Sault Ste Marie, Ontario.

My thanks to Hal Skaarup for his prompt and helpful response to my query about using an image of G-CYDU at Richibucto, N.B., which appears in his post on HS-2Ls: https://www.silverhawkauthor.com/post/canadian-warplanes-2-curtiss-hs-2l-biplane

Finally, Alastair Reeves, John Orr, Hedley Auld and R.S. Grant provided much appreciated critical reviews of drafts of this article. The author, as always, remains responsible for any errors of fact or interpretation.

As a reader, if you spot something demanding comment or correction, please use the comment box at the foot of the post to let me know.

NOTES

1. Port-Menier is now Anticosti’s only village. Total population of the island in 1921 was under 200 people, as it is in 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/L%27%C3%8Ele-d%27Anticosti,_Quebec

2. In 1983, Baie Gamache became the official name for Ellis Bay. https://toponymie.gouv.qc.ca/ct/toposweb/Fiche.aspx?no_seq=127249

3. Alfred Edward (Blondy) Wright went on to earn his commercial pilot’s licence in March 1927. He would return to Anticosti as staff pilot for the Anticosti Corporation in 1929 and 1930.

Alastair Reeves offered comments on the problems of radiator scaling in the HS-2Ls and other early aircraft. Before coolants came on the market, radiators were filled with locally available water. More often than not, this was “hard” water with a high mineral content that would leave deposits on the inner surfaces of radiators. The mineral scales had to be scraped off or flushed away with hydrochloric acid. (A. Reeves, email 21 November 2024.)

The forced landing of G-CYDU was mentioned by Fred Barriault in his interview with Luc Jobin on 27 July 1978 at Havre-Saint-Pierre. Barriault said that salt water had been used in the radiator. As a result, the engine had to be completely taken apart. It took several weeks to clean and reassemble it. See: https://www.comettant.com/entretiens-anticostiens-jobin/143-fred-barriault-27-juillet-1978-havre-st-pierre/

4. The long jetty ensured enough draft for heavily laden cargo ships transporting pulpwood to the North Shore. Flat limestone reefs extend from the shores of Ellis Bay. Near the jetty, the water is 7-16 feet (roughly 2-5 m) deep, and 16-33 feet (5-10 m) at the bay entrance. Add to this the effect of tides: the St. Lawrence is tidal from Québec downriver. For 6 November 2024, tide charts for Ellis Bay show a low tide of 1½ feet (44.50 cm) and a high tide of 6 feet, 2 inches (188.11 cm). https://fishing-app.gpsnauticalcharts.com/i-boating-fishing-web-app/fishing-marine-charts-navigation.html?title=Baie+Ellis+boating+app#10.77/49.7922/-64.3779

5. Ambrose Bernice Shearer (1893-1952) learned to fly at the Curtiss School, Long Branch, Ontario, in 1915. With the Royal Naval Air Service, he flew bombing missions in Germany and the Adriatic. In October 1918 while with No. 66 Wing, he took a bullet in the thigh and was hospitalized in Valona, Albania. He was awarded the French Croix de Guerre with Palm, the Italian Silver Medal for Military Valour and the Italian Croci de Guerra. After resigning his RAF commission in December 1919, he joined the Canadian Air Board in 1920. Posted to Nova Scotia, he served as Superintendent of the Halifax air station until November 1923. He was appointed Squadron Leader in the Canadian Air Force in January 1923. He pursued his career in the Royal Canadian Air Force until his retirement in 1944 with the rank of Air Vice-Marshal. See Memorable Manitobans: Ambrose Bernice Shearer (1893-1952) and A.B. Shearer, https://www.rcafassociation.ca/heritage/search-awards/

6. “Proposition de faire de la Baie Ellis un centre d’aviation.” Journal de Georges Martin-Zédé, 11 septembre 1922.

Georges Martin-Zédé (1854-1951) was on the Salonika Front 1915-1917 with the French Corps expéditionnaire d’Orient (later called the Armée de l’Orient). He chose to enlist at age 60, well over the age of conscription. For his service during the Macedonian campaign, he was awarded the French Croix de Guerre and the British Military Cross. In 1921, based on his war record, he was inducted as a Chevalier of the Légion d’honneur. See Quebec Chronicle, 6 February 1918, p.10 re the Military Cross.

Walter Robert Kenny (1895-1944) served as a Royal Naval Air Service pilot in World War 1. He was awarded the DFC for anti-submarine work. Appointed Air Vice-Marshal in January 1940, he was then named Air Attaché to the Canadian Delegation in Washington, a post he held until his retirement due to ill health in 1944. See https://www.rcafassociation.ca/heritage/search-awards/ and obituaries in the Ottawa Citizen and Ottawa Journal, 11 April 1944.

7. In 1968, a spelling correction changed the name of the lake to Lac Plantain. See https://toponymie.gouv.qc.ca/ct/ToposWeb/Fiche.aspx?no_seq=49800. About 3 miles (5 km) from Port-Menier, the freshwater lake provided a safe harbour for seaplanes that avoided the rocks, winds, salt water and tides of Ellis Bay.

8. “Possibilité et importance de l’aviation à l’Ile pour la surveillance, la poste, les approvisionnements, les transports des passagers des rivières et même de Gaspé.” Journal de Georges Martin-Zédé, 18 septembre 1922.

9. Lt.-Col. R. Leckie, “Flight of two HSL Flying Boats from Halifax to Roberval, July 1920.” Library and Archives Canada, RG24-E-1-a, Vol. 4991, File No. 1008-1-79.

10. See the website of the United States Coast Guard, U.S. Department of Homeland Security. https://www.history.uscg.mil/browse-by-topic/Aviation/Article/3051573/curtiss-hs-2l-flying-boat/

11. The Magnificent Distances: Early Aviation in British Columbia 1910 – 1940. Sound Heritage Series Number 28, (BC Provincial Archives) 1980. Thanks to Alastair Reeves for this reference. See p. 16 re the wires.

Bernie Shaw, in Photographing Canada from Flying Canoes, p. 17, retells the old joke about the easiest way to check the rigging on an HS-2L: you just release a pigeon from the cockpit. If the bird escapes, you know a wire is missing. (Pigeons predated radio technology: they served to carry emergency messages back to home base.)

12. Re G-CYEK accident: Proceedings of Court of Inquiry – Flying Accidents: 2 October 1922. “Accident at Godbout, Québec, 21 September 1922.” Library and Archives Canada, RG24-E-1-a, Vol. 5974, File 1021-2-13.

13. Multi-year average September sea temperatures for Baie-Comeau, Québec. https://www.seatemperature.org/north-america/canada/baie-comeau-september.htm

14. Alphonse Landry, “Preliminary Report Regarding Operations at Roberval Air Station, Season of 1922” (English translation). See Report of the Air Board for the Year 1922. Ottawa: F.A. Acland, King’s Printer, 1923, pp.47-48.

Landry (1894-1923) was one of the very best aerial timber sketchers in Canada. In 1921, he received a provincial bursary to study aerial photography in France. He was scheduled to teach forestry at Université Laval in the fall of 1923 and to become director of aerial photography for the Québec Département des Terres et Forêts when his life was cut short 26 September 1923 in the crash of HS-2L G-CYAG, based at the Roberval air station. (Alastair Reeves, email 30 June 2024.)

The flying boat went into a spin when preparing to land on Lac Saint-Jean at Roberval. The pilot, Lieutenant Bernard de Salaberry, 25, learned to fly in England in the Royal Air Force (RAF) and held Canadian civil (commercial) pilot’s licence #183 (5 May 1923). He was unable to recover from the spin. CYAG hit the water at a 40 degree angle, and broke apart under water. De Salaberry, Landry and mechanic Clifford Mallin Guise all drowned. All were single men.

A funeral with full military honours was held in Ottawa on 1 October 1923 for de Salaberry, the eldest son of Col. René de Salaberry and grandson of Lieutenant Colonel Charles-Michel de Salaberry, the hero of the battle of Châteauguay (October 1813). His remains were laid to rest in the family mausoleum at Chambly, Québec.

Landry’s funeral took place 29 September 1923 in Saint-Alexandre-de-Kamouraska, a town about 18 km (11 mi.) from Rivière-du-Loup. An impressive monument marks his grave in the Nouveau Cimitière there. (Courtesy of Pierre Verhelst, email with photo 27 November 2024.)

Guise, born in England in 1893, came to Canada in 1910. He served from December 1917 to May 1919 with the Royal Flying Corps and then the RAF as an aircraft mechanic. He was subsequently on staff with the Air Board as an air engine fitter at Sioux Lookout, Ottawa and Parry Sound, Ontario. In 1923, he was employed as an air engineer by the Dominion Aerial Exploration Company at Roberval, Québec. His funeral was held at St. James Cemetery, Toronto, on 5 November 1923. (Details of his work with the Air Board courtesy of Hedley Auld.)

A Court of Inquiry was convened on 30 September 1923 to investigate the accident, with Major Lloyd Breadner, Controller of Civil Aviation, presiding. His report can be found at Canadiana Heritage C5917, images 1432-1443 (reference courtesy of Hedley Auld). https://heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_c5917/1432

SOURCES

Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec. Journal de l’Île d’Anticosti de Georges Martin-Zédé 1922. Fonds Georges Martin-Zédé. Cote : P186,S2,D1-21.

Canada. Air Board. Report of the Air Board for the Year 1922. Ottawa: King’s Printer, 1923.

Gingras, Sylvain. L’Aventure des pilotes de brousse. Saint-Raymond, Québec: Les Publications Triton, 2001. See pp. 92-94, “Roberval.”

Library and Archives Canada. R112-392-1-E, RG24-E-2. Canada, Air Board. “Minutes of meetings of the Departmental Committee of the Air Board, August 1920-July 1922.”

— RG24-E-1-a, Vol. 4905, File 1008-3-2. “Flying Operations for Provincial Government of Quebec.”

— RG24-E-1-a, Vol. 5074, File 1021-2-13. “F3 Flying Boat – G-CYEK.” [The F3 designation is an error. CYEK was a Curtiss HS-2L.]

— RG24-E-1-a, Vol. 5075, File 1021-2-16, Vol II 1923-1930. “HS-2L Flying Boats – CAF (1920-1932).”

Newspapers of the day, notably Le Devoir, Le Droit,The Gazette,The Halifax Evening Mail, Le Nouvelliste (Trois-Rivières), The Montreal Star, The Quebec Chronicle and Le Soleil.

Reeves, Alastair. “Aerial Forest Fire Detection Patrols in Quebec: 1919.” Journal, Canadian Aviation Historical Society, Vol. 49, No. 1, Spring 2011, pp. 16-24.

Shaw, S. Bernard. Photographing Canada from Flying Canoes. Burnstown, ON: General Store Publishing House, 2001.

Terry, Christopher. Anti-submarine Warfare Pioneer to Bush Pioneer: The HS-2L in Canada. Ottawa: Canada Aviation Museum, 2004.

Recent Comments